Yidianr Dongxi

The following is the rather hasty memoir of a journey to Hong Kong and Mainland China taken during February 2003.

(Text and images copyright 2003 by Walter Jon Williams, and may not be reproduced without permission.)

Wednesday, February 12, 2003

“A little something,” yidianr dongxi, memories of my Asian adventure.

I was met at the Hong Kong airport by Erick Wujcik , who had offered to play host while I was in town. I’m not sure how to describe Erick to those who haven’t met him. He’s bigger than me, heavier than me, furrier than me, jollier than me, and more enthusiastic than me. He is a connoisseur of Weird Stuff and Odd Angles. He carries about him a permanent aura of benign disorder and constant flux.

If Erick were a D&D character, his alignment would be Chaotic Good.

Erick turned up at the Lantau airport with a complimentary Hong Kong Starter Kit. This included a cell phone, a street guide, a bus schedule, and my Octopus Card. The Octopus Card is one of those marvels of Hong Kong— it’s good for rides on all buses, subways, and ferries (all of which are amazingly cheap). You add cash to the card at machines in the subways or at any 7-11. (Yes, there are 7-11s in Hong Kong. One on every block, just about.) You can also use the card to pay for anything you happen to buy at a 7-11. It’s a brilliantly efficient idea.

The tentacles of the Octopus, we should note, will soon get a lot longer. The next version of the Octopus will also serve as the user’s drivers’ license, bank card, and official Hong Kong ID. Medical and police records are only a matter of time. Thus the amazingly convenient transport

card will turn into what is potentially the key database element of a surveillance-based totalitarian state. With a few strokes of a keyboard, the Authorities will be able to tell who you are, where you’ve been, how you got there, how much money is in your bank account, and where it came from. Match that with the video cams strung up in many public places and, hey, Hong Kong becomes a lot more, umm, “orderly.”

I collected some Hong Kong dollars from an ATM and used the Octopus to board the Airport Express, a fast subway that took us to Kowloon Station, on the waterfront facing Hong Kong, and from thence by cab to the hotel Erick had found for me, the Concourse, in the heart of Mong Kok, which is itself the heart of Kowloon. The Concourse is a block from Nathan Road, which is Kowloon’s main street, and in the midst of a deeply funky district, expensive shopping malls mixed with lots of street cuisine, highly specialized local markets, Triad-run massage parlors, and a rather staggering number of travel agents (none of whom, by the way, spoke English).

The hotel was a fairly basic Western-style hotel, with a customer base of mostly Chinese and Japanese. The water was not potable, so the first errand was across the street to the 7-11 for some bottled water.

By this time it was after midnight on a week night. The streets were still very crowded and no one had turned off any of the neon. Erick decided to take me on a tour of the neighborhood, showing me items of interest to the tourist (subway stops, bus stops, how to read bus schedules), and

pointing out a local flyover.

Flyovers are all over Hong Kong. With crowded streets and lots of traffic, the Hongkies have moved the pedestrians upstairs, in long, covered, suspended overhead passageways (usually) reached by escalator. It’s an efficient, if ugly, solution to the traffic problem.

Erick, with his usual great enthusiasm, was explaining this and many other things, and politely ignoring the fact that, after 20+ hours in airplanes and airports, I had completely lost the ability to walk in a straight line. The locals seemed fairly tolerant of the big American and his drunken,

weaving friend.

The thing that sticks in my mind from that walk wasn’t the traffic or the neon or the crowds or the flyovers (which I have always heard called honkie tubes), but a stroll through the nearby goldfish market. There were 24-hour goldfish stores still open, just in case anyone needed a carp at 3 in the morning. The notion that there were enough such people in Mong Kok to support 24-hour goldfish stores was my first real clue that I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

At this point I began to list rather heavily to starboard, and insisted on going to bed.

In order to successfully negotiate the 16-hour timezone change, I took a sleeping pill, some melatonin, some aspirin, and a tagamet. As a result I slept rather late the next morning.

From my hotel room I looked down at the depressing sight of Hong Kong worker housing, shabby-looking, dirty apartment buildings strewn with laundry and festooned with wires and cables. These places might not have been as depressing as they looked, however— Chinese people seem not to care much about the outsides of their buildings, and the insides might have been bright and well-looked-after.

However you looked at it, Mong Kok did not look as attractive in the daytime as it did at night.

Erick described Mong Kok as “the most Cantonese part of Hong Kong,” but to me it seemed the most multicultural, assuming you understand that the cultures involved are all Asian. There seemed a wider variety of ethnic and racial types (all Asian) than in the more fashionable areas, more buzz, more varieties in the biz.

And there were TWO kinds of internet parlors. Some had naked women, and some didn’t. At the first type, you pay to sit at a monitor and watch a woman in the next room take off her clothes. This I found another one of those Weird Cultural Moments. The only way I can figure this one out is

that some people are so used to getting their erotica over the computer that the computer itself has become eroticized, and they would rather watch naked women on video than watch actual naked women (who are also available, of course, at the nearby Triad-run massage parlors).

The type of internet parlor that you actually want, it turns out, has the English word “games” on the sign. It’s here that you can surf the Web and send email messages. I don’t know whether this is a comment on whether porn drives the web or not, but I could never find an actual non-naked-lady internet parlor that was actually open for business. In an area with 24-hour goldfish stores, this is a surprising lack.

Mong Kok is more or less in the center of Kowloon, the peninsula on which most of the seven million inhabitants of Hong Kong live and work. Hong Kong island itself is at a disadvantage, since it’s (a) an island, (b) smallish, and (c) distressingly vertical.

Kowloon is a corruption of the Cantonese gai lung, meaning “Nine Dragons.” Eight of the dragons are the mountains behind the peninsula, and the ninth is the last emperor of the Song dynasty, who was driven to Hong Kong by Mongol invaders under Kubilai Khan. After a naval battle off Hong Kong, in which the remnants of the Song fleet were defeated, the young emperor committed suicide, along with many of his subjects. He sleeps in the sea off Kowloon, and is commemorated by its name.

(The name may also have something to do with the Nine Little Boys of the Earth Dragon, of which more anon.)

After rising I called Erick to find he was working his usual 12-hour day at Hong Kong Polytechnic, where he teaches computer game and media design to classes of hip, polyculturally savvy young geniuses. His steady, Kate, agreed to look after me for the day, and introduce me to Hong Kong island itself. So I had a peanut butter granola bar I’d carried from the States and set off.

It took me a long time to find the nearest subway station, less than a block from my hotel, because I got confused whether I was traveling north or south. This was a perpetual problem, as it turned out. Hong Kong was usually misty and cloudy, and I rarely saw the sun. Surrounded by tall buildings and with no way to see a horizon, I was frequently disoriented. Since I’m normally a person who finds his way around in strange cities very easily, this was disturbing. (Or I’m getting senile, in which case I won’t be disturbed by this for much longer.)

I finally found Prince Edward Station and got on the MTR for Hong Kong Island. (The MTR is the subway, whereas the KCR is the light rail that travels from Kowloon through the New Territories to the Chinese border.) It’s easy for westerners to find their way around Hong Kong: all street signs and directions are in Chinese and English, and announcements on the MTR are in both Cantonese and English. (On the KCR they add Mandarin, because of the people coming over the border from the mainland.)

I finally found Prince Edward Station and got on the MTR for Hong Kong Island. (The MTR is the subway, whereas the KCR is the light rail that travels from Kowloon through the New Territories to the Chinese border.) It’s easy for westerners to find their way around Hong Kong: all street signs and directions are in Chinese and English, and announcements on the MTR are in both Cantonese and English. (On the KCR they add Mandarin, because of the people coming over the border from the mainland.)

I got off in the vast, wandering artificial caverns of Central Station, which was in short order going to become my least favorite place in Hong Kong, and then took the long, long, long, long tunnels to nearby Hong Kong Station (on another branch of the MTR), where I travelled back to Kowloon, and up to the Waterfront high-rise development, where Erick and Kate live with Erick’s cousin Steve and Steve’s son, Zack.

Kate, whose name is spelled “Kate” but pronounced “Kay” or perhaps just “K.”, like a character out of Kafka (even Erick is a little vague on this matter), is a lovely lady who managed my arrival on her doorstep with gracious aplomb. As the day progressed I realized that though it was Erick who had invited me to Hong Kong, he was working 72-hour weeks at Polytech and it was Kate who was actually stuck with me. I vowed to be as light a burden as possible and to buy her something nice by way of thanks.

We headed back to Kowloon Station and from thence to Hong Kong  Station on the island, then down the long, long, long, long tunnels to Central Station, then down more tunnels and up escalators and across balconies and along flyovers (pant pant) to Mid-Levels, an area of shops and restaurants on the steep hillside behind the pricey shopping malls and mass transit centers of Central. Fortunately once you reach Mid-Levels most of the actual climbing is done by escalators and slideways. (Getting down, you’re mostly on your own.) Kate was trying to find a dumpling restaurant for our lunch, and there was considerable crosstalk on cellphones between Kate, Erick, Steve, and myself before we realized that we’d gone ‘way too far and had to backtrack to the sign for the kinky leather bondage store (no exciting window displays, alas), and that the dumpling place was just beyond it.

Station on the island, then down the long, long, long, long tunnels to Central Station, then down more tunnels and up escalators and across balconies and along flyovers (pant pant) to Mid-Levels, an area of shops and restaurants on the steep hillside behind the pricey shopping malls and mass transit centers of Central. Fortunately once you reach Mid-Levels most of the actual climbing is done by escalators and slideways. (Getting down, you’re mostly on your own.) Kate was trying to find a dumpling restaurant for our lunch, and there was considerable crosstalk on cellphones between Kate, Erick, Steve, and myself before we realized that we’d gone ‘way too far and had to backtrack to the sign for the kinky leather bondage store (no exciting window displays, alas), and that the dumpling place was just beyond it.

The dumpling restaurant— it had no name in English, just a sign in Chinese with the two English words “homemade dumplings”— was a typical narrow place of formica tables and bright fluorescent light. I had the Beijing-style dumplings (pork, I think), with noodles, in broth, and iced tea, which in Hong Kong comes in cans and is not brewed fresh. Since it’s impossible to make a polite meal of noodles eaten with chopsticks, I slurped away with gusto and enjoyed myself hugely. The dumplings were very fine. The Mid-Levels are a kind of Foreign Restaurant Quarter, with whole streets devoted to Italian, Vietnamese, Thai, or Irish Pub cuisine. Our little Cantonese dumpling shop outshone them all.

After lunch, we wandered in search of a health food store, where Kate bought some ear candles. These are long, hollow, flammable objects which you stick in your ear and then set on fire. The treatment is said to rectify the spirits. After the dumplings I felt that my spirits did not require rectification, and so I didn’t purchase any myself.

We wandered along the endless ramps and corridors and tunnels of Central again— already I was getting tired of the place— and then got on the Star Ferry for Kowloon. The Star Ferry has been running ever since the British acquired Hong Kong, and is justly famous. This pleasant 19th century mode of transportation took us across the harbor in a few minutes and gave us spectacular views of Hong Kong and Kowloon along the way.

Architecturally, the remarkable thing about Hong Kong is the enormous height of its apartment buildings. They’re fully as tall as the office skyscrapers. If there’s anywhere else in the world where people actually choose to live in apartments the size of the Woolworth Building, I haven’t

seen it. And the apartment buildi ngs go up and up, up the steep mountain sides of the island, row after row of them.

(And it’s a little unsettling, if you get to the top of the mountain, to look down on buildings that tall.)

There are relatively few old buildings in Hong Kong, and even fairly new buildings are regularly knocked down to build newer, bigger ones. Very little is allowed to get in the way of the real estate market. Hong Kong is all about money. Money is what people come there to get, and all other considerations are put firmly to the side.

Not but that the buildings don’t have their entertaining side. Many of the big office buildings have been turned into brilliant light shows. Entire flanks of the buildings have been covered with colored lights that flash animated displays. It’s like the first scene in Bladerunner , with huge video and sound displays looming down in the little noodle sellers below, in the rain. Except it’s beyond Bladerunner now: Sir Run Run Shaw was filming the Hong Kong he could see on his near horizon, but that horizon’s well past. Times Square has a quaint early 20th Century feel by comparison.

From the Kowloon Star Ferry terminal, with its famous clock tower, we journeyed along the coast of Kowloon past the modernist turtle shell of the Cultural Center— something that might have been designed by Eero Saarinen— where we checked for upcoming shows. The Rolling Stones, the Paris Symphony, and King Lear done as a Cantonese opera. I thought about attending that, since I at least knew the plot, but grew less enthusiastic when Kate told me it was a one-man show. She’d recently seen “Heroines of the Chinese Opera,” an all-fighting, all-gymnastic spectacular, but alas it was no longer in repertory.

Construction turned us inland, and we passed the Peninsula Hotel, one of the grand old buildings that has actually survivied. It’s the priciest hotel in Hong Kong, and its afternoon high teas, which cost something like $165 American, are quite famous. I was virtuously content with my $3 bowl of noodles.

Much of Hong Kong has a faintly repellent smell, a combination of diesel exhaust combined with chicken and duck fat dripping from the fowl hung up in the restaurant windows. A Hongkie would find the smell homelike and wonderful, I’m sure. I found it just slightly nauseating.

We continued on to East Tsim Sha Tsui, another district of Kowloon, where we checked out the Hong Kong History Museum, which had a special display on the terracotta warriors of Xi’an (at least some of which turned out to be copies, as I discovered later). The warriors were quite magnificent, though, and helped me make up my mind to visit Xi’an.

Eventually we met Erick for dinner at the Garlic Factory, a neo-Japanese place in Tsim Sha Tsui. We had garlic pizza, which isn’t anything like Western pizza but a crispy crackerlike crust drizzled with garlic mayonnaise and slices of fried garlic. We also ate grilled steak sliced thinly and covered with mushrooms and garlic, and slices of eel grilled on a stone heated to 300-degree Celcius, then added to an earthenware pot in which rice was cooked in a tangy sauce . . . very Iron Chef-like. We had other things as well, none of which I remember. Afterwards Erick suggested going up Victoria Peak to see the sights of the harbor below, but I was tired and demurred.

On the way to my hotel, I stopped at the 7-11 to pick up bottled water and a large bottle of beer, which eased my way toward slumberland. My first day in Asia had come to an end.

Thursday, Feb 13.

The morning was spent with travel agents in Mong Kok, trying unsuccessfully to arrange side trips out of Hong Kong to the mainland. Though Mong Kok was crawling with travel agents, one or two every block, I failed to find anyone whose English skills were up to my needs. Even the travel agent in my hotel was a little dicey, but the only trip she had to offer was one to Shenzhen, an industrial city right across the border.

Shenzhen, however, has an attraction in which all the major tourist attractions of China are beautifully reproduced in miniature. To go to Shenzhen is to see every beauty spot in all of China! Why would you ever go anywhere else? Especially as Shenzhen also has an exhibition of world tourist attractions! I could go to Shenzhen and see Mount Rushmore! Probably there are even places marked on the floor where I could be photographed at Mount Rushmore!

I rather spoiled the party by insisting on seeing some actual spots in China. Obviously Mong Kok wasn’t up to the job.

Erick had told me that trips to the Mainland were easy, cheap, and plentiful from Hong Kong, and that all I had to do was a little shopping around to find a series of wonderful bargains. While this was perfectly true, it was also impossible. I didn’t know which travel agents catered to foreigners, or where they were, or what packages they were offering. The time I spent shopping around for bargains was time that I could otherwise have spent enjoying Hong Kong. I discovered later that my best chance was to go to the island, to an area covered by tourist hotels like Causeway Bay, and deal with companies like American Express . . . but this was later. It would have been better had I arranged the trips through the Web, before I ever left the States.

In fact I went to the island, but to the wrong part, to Sheung Wan, on the western side of the city, where I knew of a travel agent that catered to foreigners (or at least had an English web page). Once there, I found the building the travel agent was supposed to be in— Erick’s map had an

index to major buildings, very handy— but the travel agent seemed not to be therein. I declined to search a 50-storey office building floor by floor, and betook myself off to local tourist sites.

Sheung Wan is an area filled with specialty markets. Chinese markets tend to clump up by category— I assume there are some economies of scale involved, or perhaps everyone expects that if you want some dried squid, you head off to Dry Squid Street in order to compare and contrast the wares of the 50 dry squid dealers with shops therein.

So I first went to the Western Market, no longer a market but one of Hong Kong’s rare historical buildings, a two-storey 19th Century brick colonial structure with arched windows that looks as if it could have been transplanted from lower Manhattan. Unfortunately the Hong Kong government planted some kind of huge metal air intake, perhaps for the subways, right in front of the building, ruining its appearance.

From thence, grumpy, I went to Wing Lok Street, otherwise known as Ginseng and Birds’ Nest Street, because that’s where the dealers of those particular items congregate. Narrow shops with narrow counters, birds’ nests in huge baskets— buy them by the hundred!—  ginseng dried, or in

ginseng dried, or in

tonic form, or pills, or tea, or wine. Large, old, venerable ginseng plants were shown, under glass, in shop windows. I know these can go for $75,000 apiece in California— I wondered what they were worth here?

From Wing Lok Street I journeyed to Dex Voeux Road West, otherwise known as Dried Seafood Street. The same narrow shops, the same counters, the same baskets full of items. The smells were rather different, and the sights. Colossal amounts of dried fish, and squid, and seahorses, which are being endangered throughout Asia because of their alleged ability to cure sexual dysfunction. Let the Chinese have Viagra! I say. Leave the acquatic animals and the rhinoceri alone!

From Wing Lok Street I journeyed to Dex Voeux Road West, otherwise known as Dried Seafood Street. The same narrow shops, the same counters, the same baskets full of items. The smells were rather different, and the sights. Colossal amounts of dried fish, and squid, and seahorses, which are being endangered throughout Asia because of their alleged ability to cure sexual dysfunction. Let the Chinese have Viagra! I say. Leave the acquatic animals and the rhinoceri alone!

Right nearby was Ko Shing Street, aka Herbal Medicine Street, with more baskets of less identifiable objects, but lots of them. And lots of different smells, of course.

From here I wandered through Hollywood Road and Upper Lascar Road (aka Cat Street), which constitute a vast flea market, selling beads and buttons and old jade, brass nicknacks and rusty old Mao buttons, statues of the Buddha and of Taoist gods, fans and good luck charms and jewelry. Behind the street vendors and their carts were much tonier establishments selling gorgeously expensive art and furniture.

I looked at some stuff with thoughts of buying gifts for Kathy, but didn’t really find anything that I knew she’d like. I didn’t think the Mao buttons were really her style.

I climbed some steep streets to the Man Mo Temple, a Taoist establishment catering to Man and Mo, the gods respectively of literature and of war, a combination that no doubt tells you something about the Chinese mind, though exactly what I will not venture to guess. I was led to the temple by vast gusts of sandalwood incense that bloomed out over the neighborhood. Chinese gods seem to live entirely on sandalwood incense, though if I were Buddha I’d want more variety in my diet.

Chinese-style temples are all built more or less alike, and Man Mo was no exception. They are not solemn places in the way that Western churches are— they’re garish, for one thing, splashed all over with red and gold and other bright colors. People are forever thumping drums or ringing bells. I saw few people that could be identified as clergy— most of the officiants seem dressed casually in street clothes.

Chinese temples are divided into three rooms, with the main object of worship in the central part, and subsidiary dieties in the two wings. Before the gold statue of the god is an altar, and before the altar are kneeling cushions so that people may kowtow to the god should they be so inclined. Usually there are gold god statues all over the place, to the sides and sharing the main dais with the main god. Somewhere will be a counter where people can buy incense and other paraphernalia. In front, outside the building, will be large stone or concrete censers (don’t know what else to call them) in which people can stick their incense. There are also elaborate cast-iron furnaces in which used incense, or other offerings, are burned.

The locals salute the gods in various ways. Most casually, they face the god, or the door to his temple, hold their hands in the prayer position, and bob toward the god two or more times. Very often they will do this with burning incense sticks in their hands, then plant the incense sticks

in the various censers standing about. Or they will hold a circular container that itself holds the incense sticks, and bob the container so that the incense rattles against the container and presumably attracts the attention of the god. (I saw one young lady do this inexpertly, with the result that burning incense sticks flew out of the container and over the base of the altar, much to her embarrassment.)

This last can also be a method of divination. Each stick is numbered, and when one falls out, you take the numbered stick to one of the diviners around the temple, who will tell you whatever it means.

Others knelt before the god, or kowtowed, or prayed with fervent concentration.

“Smoke towers” hung from the ceilings. These are spirals of incense suspended from the central part, so that the rest dangles down cone-fashion. These are lit from below and burn for several days before being replaced. If you stand under them you get incense in your hair.

You don’t do Chinese religion unless you really like the smell of sandalwood.

Since the New Year’s celebration was still going on— it lasts half a lunar month, this year from 1 February to 15 February— all China’s temples were doing a roaring business. Red lanterns were strung up everywhere. Traditional offerings of fruit— usually oranges— stood in little pyramids on most of the altars, and before the guardian lions at the doors (who also wore, as part of their New Year’s paraphernalia, red ribbons with a kind of rosette on the chest).

New Year’s is also the traditional time for visiting one’s family, including those who happen to be dead. Temples sell kits in aid of this, boat-shaped wicker baskets filled with various paper offerings to dead relations. There was spirit money, on which one wrote the name of the deceased for whom the money was intended, rather like a celestial money order. These were folded in a particular way to form a boatlike shape. There were other, more obscure items in the ancestor kit, including some things that looked like paper snowflakes only black.

Kate bought one of these before I arrived, and sent money to her deceased relations (except for one ancestor who was a son of a bitch and would just have to go without). She had no real instructions on how to prepare the offerings, but fortunately her housemaid was able to help her out.

(Note: this episode became the foundation for the excellent story “Ancestor Money,” by Maureen McHugh.)

The temples I visited had whole stacks of these boats sitting on shelves awaiting incineration. The dead would have to wait for the celestial wire to clear before the money could be sent to them.

This led me to Mid-Levels again, where I looked about for a late lunch. The dumpling shop of the previous day was packed, with no hope of getting a table for a while. None of the other restaurants seemed to be actually Chinese, and I thought I’d want Chinese food, as I was in China an’ stuff. I ended up at a different dumpling restaurant in Kowloon, which was pleasant and filling though not as good at the place Kate found.

That night I met Erick and Kate for dinner at a seafood place, the London Restaurant, though what it had to do with London we could not see. We were the only roundeyes in the place, which struck us as a good omen. We had many delightful items, including a whole fish steamed in banana

leaves.

It’s bad juju in China, by the way, to turn the fish over. You have to just eat clear down to the bottom through the top, unless a waiter notices your predicament (as happened here) and flips the fish for you. Eating with chopsticks makes it rather more challenging.

You also should not point the teapot at anyone, because “to point the teapot” is a homonym for “to die the death of a thousand dogs,” or something to that effect. In restaurants, as a matter of politeness, I found myself constantly trying to avoid sending deadly teapot rays at other diners.

(As an aside, I should mention that though I am an adventurous eater, there were certain items I tried to stay clear of. Anything with “fish maw,” for example. Or “chicken paw.” Or tripe. Though I was tempted to try the tripe, as every so often I enjoy menudo, this being a New Mexican specialty.)

From the restaurant we returned to Hong Kong Island for the cable car ride up Victoria Peak. The cable car was a genuine cable car, like those in San Francisco, toiling up a very steep incline, with apartment buildings on all sides. The terminus on Victoria Peak was a shopping mall filled with boutiques and restaurants. Erick knew of a place outside the terminus with a better view, and this we found.

There was Hong Kong below us, with Kowloon beyond, an amazing array of pastel lights, with animated New Year’s displays flashing and dancing over the harbor. To one side was Aberdeen Harbor, with the famous Jumbo floating restaurant, a huge neon-lit Chinese palace built on a barge.

There was Hong Kong below us, with Kowloon beyond, an amazing array of pastel lights, with animated New Year’s displays flashing and dancing over the harbor. To one side was Aberdeen Harbor, with the famous Jumbo floating restaurant, a huge neon-lit Chinese palace built on a barge.

From on high Hong Kong looked less like a real city than the setting for a brilliant, hard-edged science fiction film, a mammoth CGI display rather than a real metropolis created by an unlikely combination of greed, politics, and human will. All the weird, funky human bits, the Dried Fish Market and the golden Taoist gods, were invisible, and from the peak you see only the colossus, the great neon-lit economic engine that drives Hong Kong to its inevitable collision with whatever destiny waits in the distant reaches of the new century.

And then we took the bus down to the human level again, a winding ride down hairpin curves in the dead of night, past the slumbering estates of the city’s plutocrats to the echoing diesel-filled concrete of Central Station, and the crowded ride home on subway cars packed with the city’s sleepless multitude.

And then we took the bus down to the human level again, a winding ride down hairpin curves in the dead of night, past the slumbering estates of the city’s plutocrats to the echoing diesel-filled concrete of Central Station, and the crowded ride home on subway cars packed with the city’s sleepless multitude.

Friday, Feb 14

Valentine’s Day is a big deal in Hong Kong, the more so this year because it came on the day before the Lantern Festival, which is the Chinese Valentine’s Day. So everywhere I went for two days I saw cute young couples holding hands, or smooching on the subways. I began to miss Kathy a lot.

Most of the day was spent squaring away my travel arrangements. Erick had emailed someone in the States who he remembered as having a good deal with a travel agent, and the person remembered what building the travel agent was in , but not its name. We went to the building but were unable to find a travel agent therein, but across the road was a division of CITS, the China International Travel Service, and they proved to have a single clerk who, if not precisely fluent in English, at least had sufficient English to sell me tickets and take my credit card.

What I found was this: the cheap package tours leave on Friday and on Monday, and it was already Friday. The places I particularly wanted to visit were Xi’an, former imperial capital and home of the terracotta warriors, and Guilin, which is the area in south China with the incredible, surreal mountain scenery seen on old Chinese paintings. (Many people assume that the scenes on those artworks are invented, but they’re real.)

CITS offered two-night packages to each, but I wanted to stay longer, to allow for more than just a single day of sightseeing in between travel days. If I left the following Monday for Guilin, then stayed three nights, I’d get back on Thursday, which left one night before leaving for Xi’an the

next day. This also left no time for my tickets to get printed— apparently tickets are printed in some central location and shipped to the travel agencies, and electronic reservations aren’t done on the cheap package tours. What I should have done was come earlier in the week and spent both weekends out of town. As it was, I didn’t relish two trips back-to-back, with no time to do laundry in between, so I settled for Xi’an the following weekend.

Guilin will have to wait for another trip.

I also had to get a visa for the mainland, which I did at the official Chinese travel agency. Less English competence here, and a group of people who got their jobs because somebody in the family was in the Party. They weren’t particularly competent, and lost my passport at least once,

but they seemed pleasant enough. And there was one sharp old guy who quizzed me about my views on the war with Iraq. (Since the China Daily was against it, so was I.) I also knew better than to put my occupation as “writer,” as the reflex of authoritarian regimes is always to view writers enemiesso as far as the visa application goes, I was a teacher.

That evening Kate, Erick and I went to a movie at Hong Kong Polytech. The English department was sponsoring an English-language film series, with a discussion afterwards, as a way of improving students’ English skills. Tonight’s film was “Bend it like Beckham,” a film not yet released in the States.

But beforehand we had speeches by students and the faculty sponsors— this was an anniversary of the film club or something— and all the members of the club got introduced, and then there was a brief skit involving a soccer ball by a couple of the students. (One has to remember that the principle point of this was that everyone got to practice their English.) The two girls with the soccer ball were grad students but looked and acted about fifteen. The Chinese have a way of preserving innocence in their children that Americans have lost, which is one reason why the Valentine’s Day lovers in the subway looked so darn adorable. Compared to these kids, American grad students look like fifty-year-old heroin junkies.

By the way, I had never heard of Manchester United star David Beckham until I saw this film, and suddenly I couldn’t get rid of him. He was on every Chinese newscast, and in every Chinese newspaper, aided by a scandal in which his coach kicked him in the head and, no doubt, by the fact he married a Spice Girl. The Sexy one, I think, certainly not the Sporty.

I had to return to the soccer-denying States before I got Beckham out of my life, and none too soon.

February15

I spent most of the Lantern Festival wandering around a number of Kowloon markets. As I mentioned, certain Chinese businesses tend to clump together, and a number of these were near my hotel.

I started at the Flower Market, which was doing a brisk business during the double Valentine’s/Lantern Festival holiday. Florists are pretty much the same everywhere, and the unusual thing about these was that dozens and dozens of them were clustered on just a few streets. There were a few unique features, such as living pagodas made up of bamboo . . . I wondered if it was a New Year’s thing, or whether these were available year round. And on one occasion I turned a corner and there were dozens of bonsai sitting in an open-air stall, all of them lovely and old and obviously well-tended. Nobody was looking: I could have tucked one under each arm and slipped off to the hotel.

Unfortunately I couldn’t buy Kathy flowers, and had no way to ship home stolen bonsai, so I went on to the nearby Yuen Po Bird Garden. It is a Chinese tradition to take your pet birds for a walk, usually in a handmade wooden cage, and this was a place where folks could take their birds. It was new, built to replace an older garden that is probably a high-rise now, and is very well-designed, a lot of traditional Chinese architectural features reproduced mostly in poured and sculpted concrete— it’s a little grey, but graceful nonetheless.

There were trees and lines on which folks— mostly older gentlemen— could hang their cages while they chatted with each other, and there was also a busy, bustling, crowded market where birds waited to be sold in bamboo cages. There was a lot of lively, colorful feathered life on display, and a good many flocks of wild birds come to gobble spilled seed. Grasshoppers were on sale as bird food. Someone told me that endangered species were sold here illegally, but nobody sidled up to me offering me an illegal bird, so I wouldn’t know.

There were trees and lines on which folks— mostly older gentlemen— could hang their cages while they chatted with each other, and there was also a busy, bustling, crowded market where birds waited to be sold in bamboo cages. There was a lot of lively, colorful feathered life on display, and a good many flocks of wild birds come to gobble spilled seed. Grasshoppers were on sale as bird food. Someone told me that endangered species were sold here illegally, but nobody sidled up to me offering me an illegal bird, so I wouldn’t know.

One of the nice things about Hong Kong is that there are little parks and garden scattered about, even in the busy, crowded districts. You just come across them in your wanderings, and they’re all worth spending a little time in. Most include a water feature, a waterfall or cascade, and I

suspect that’s not only because it’s good feng shui, but because the sound of the water helps to drown out the traffic noises being generated only a few yards away.

Speaking of gobbling insects, on the way back to the subway stop I passed the shop of the Ant King, who sold ants for people to eat. Traditional Chinese medicine involves balancing heat and coolth, and ants provide heat, so if you’re in danger of being overcool, ants are recommended to spice up your diet. The Ant King sold not only ants, but ant extract and ant wine.

I took the subway a couple of stops to Tsim Sha Tsui, where I wandered through the Shanghai Street Market. This sold mostly food, but also nicknacks and whatnots. Among the food items were stacks of squashed duck, cooked or smoked ducks flattened to the shape of a frisbee for easy transport. Apartment buildings towered on all sides of Shanghai Street, which provided an interesting contrast. I liked the fact that I was in a modern city, with high-rises and ubiquitous communication and mass transit, but below in the shadows of the buildings were a whole series of these human-scale, functioning markets, with stalls and venders selling many of the same items that would have been sold a hundred years ago.

From Shanghai Street I meandered to the Tin Hau Temple, dedicated to the Taoist goddess of the sea. Tin Hau’s story is this: she was a young girl who needed transport to one of the local islands (probably for some kind of filial duty, I don’t remember). All the junk captains refused her a ride,

so she went on a little sampan. A storm blew up and all the junks were wrecked, but the sampan survived, and when Tin Hau stepped ashore, she went to the top of a local peak, golden beams shot down, and she was translated straight to Heaven.

There are temples to Tin Hau all over Hong Kong and its territories, mostly built on what once was the waterfront, but is no longer— much of Hong Kong is built on fill. Kowloon’s temple is very much landlocked by now, with tall buildings on all sides, but it’s a large, spacious place, with a generously-sized park out front, with banyans and much shade. The temple was doing a roaring business on the last day of the New Year celebration, and many gusts of sandalwood were sent heavenward. This was the only temple where I actually saw a ceremony being performed: there was a man (in street clothes) chanting and beating some drums, presumably in honor of the ancestors of the gentleman who stood respectfully by and who had paid extra for the privilege.

South from the Tin Hau Temple stretches Temple Street, home of the most boisterous night market in Hong Kong, where the party goes on till the wee hours. I visited it later in my journey.

On this particular afternoon, however, I strolled on to the Jade Hawkers’ Market, which is contained in several large tentlike buildings. Hundreds of jade hawkers have their stalls here, selling every kind of jade item imaginable: jewelry, sculpture, amulets, beads. Every source I consulted told me that it was unwise actually to buy jade here unless you happened to be a jade expert, so I confined myself to gawking at the beautiful, intricate carvings, the buddhas and lions, the spheres carved inside one another, the stunning jewelry, all in green and amber and yellow and

milk-white.

After that, I was footsore and hot and wanted ice cream and a nap, both of which I hastened to procure.

That night I assembled with Erick and Kate and Zack and Steve for the official Lantern Festival, which was held in a park amphitheater. The cab driver seemed a little surprised at five gwailo going to a Chinese festival, but he was a cheery, talkative sort who delivered us right to the park

entrance, thus avoiding the long, long lines of people who waited on the streets, penned up by police, and who were dribbled into the park in small numbers so as not to overcrowd the place.

Entering the festival we passed by dozens of imaginative lanterns in the shape of insects, fish, and animals, all lit by electricity unfortunately. We acquired popcorn and soft drinks from vendors and headed to the amphitheater where entertainment was going on. There were lots of red lanterns strung up, big red New Year pagodas, and occasional fireworks. The entertainment was traditional Chinese music (we had been promised acrobats, but didn’t get any) and then, over to one side, was the quiz show.

Lantern Festival is a traditional night for blind dates, and one of the things you do with your blind date is go to the quiz show, where you are given forms in which you try to explain the origins of obscure Chinese words. This is to discover if you and your date are compatible. This strikes me as perfectly reasonable: for example, I myself am never seen in the company of a woman who can’t define “matutolypea.”

The Lantern Festival began to lost its energy when one dignitary stood to introduce a bunch of other dignitaries, all of whom then had to give little speeches. Even though I didn’t understand the Cantonese, it was clear that none of these people were professional speakers, and that none had

heard the maxim, “Keep it brief.”

The Lantern Festival was sort of stuck between two poles. It was too electric and modern for it to be charmingly traditional, but it wasn’t Hollywood enough to really grab your attention. When another traditional orchestra mounted the stage and began to play, we wandered off past the long lines of people waiting to gain admittance, found a cab, and went to a most excellent dinner.

February 16

On Sunday I decided to visit what all the Westerners seem to call “Big Buddha”— the giant bronze Buddha statue on the Po Lin Monastery on Lantau Island. Lantau is larger than Hong Kong island, but with few people. Most of it is wilderness reserve, with hiking trails and camp sites. The Po Lin Monastery is at the mountainous heart of Lantau, surrounded by craggy limestone peaks and spectacular vistas that reach all the way to the sea, all the stuff of Chinese paintings.

And as for Big Buddha himself, he is (as the tourist brochures never cease to remind us) “the world’s largest seated freestanding Buddha.” You would think that “seated freestanding” would be a contradiction, but apparently it’s not.

The ferry ride to Lantau is supposed to feature spectacular scenery, but it was misty that morning and I saw none of it. The ferry landed at the small town of Mui Wo, also known as Silvermine Bay, which (in the brief time I spent there) did not look terribly interesting. I hopped on the Number Two Bus, which loaded with tourists began the long, winding trek into the hills.

Most of the scenery was lovely and unspoiled, and even the developed bits had a spectacular side to them— the road went along the top of a massive earthen dam that held the island’s reservoir, and I looked at the high-rise, ocean-front apartments built below and wondered how long till the next earthquake.

The central part of the island is quite uninhabited, and if you want a place for an isolated monastery you can’t do better than Po Lin, several thousand feet into the mountains and surrounded by picturesque, mist-enshrouded peaks. But Po Lin has always had ambitions that transcended its isolation: the monastery’s own guidebook admits that it was founded (around 1900) with the intention of becoming a “rich monastery,” and they’ve obviously succeeded.

Indeed Po Lin was so colorful and crowded that it was easy to think of it not as a religious institution, but as Buddha-Land. The first thing I saw as I left the spacious parking lot was a large group of middle-aged ladies doing a synchronized flag dance in front of the main gate. I have

no idea why. All I knew was that it wasn’t martial arts, and it didn’t seem overtly devotional either.

Big Buddha Himself is on a cone-shaped hill reached by a broad stairway with 260-odd steps. The stairway is decked with colorful flags and with small pagodas and incense burners for folks who want to make offerings on the way. He sits over 20 meters tall on a bronze lotus blossom, with his usual serene smile and with one hand raised in what might be called the “Mudra of Howdy.” The other hand is open on his lap. On both palms are carved symbols representing the treasure Buddha offers humanity. On his chest is a swastika (in Buddhism a symbol of wisdom), and his earlobes are huge and pendulous (a symbol of wisdom in China).

Big Buddha Himself is on a cone-shaped hill reached by a broad stairway with 260-odd steps. The stairway is decked with colorful flags and with small pagodas and incense burners for folks who want to make offerings on the way. He sits over 20 meters tall on a bronze lotus blossom, with his usual serene smile and with one hand raised in what might be called the “Mudra of Howdy.” The other hand is open on his lap. On both palms are carved symbols representing the treasure Buddha offers humanity. On his chest is a swastika (in Buddhism a symbol of wisdom), and his earlobes are huge and pendulous (a symbol of wisdom in China).

Big Buddha is cast bronze on a frame of steel. He was finished in 1997— when I set out to visit him, I didn’t realize he was so recent.

On Buddha’s head are rows of knots that have traditionally been explained as a colony of snails that Buddha in his compassion allows to live on his scalp, but which in fact are the curls of the Greek god Apollo. When Alexander the Great entered Southwest Asia in the 4th century BC, he brought with him hordes of artisans and sculptors who commenced the Hellenization of his conquests, and who planted temples to Apollo and the other Greek gods in exotic places north and west of Persia.

Buddhists had not to that point represented Buddha in their art, but they liked the look of Apollo, and soon Buddha was represented as a lithe, curly-headed young man with the muscled torso of a Greek runner. As the years went by and Alexander and his works faded from memory, Buddha’s statues began to develop more Asian features and musculature, and Apollo’s curls were reduced and stylized to the point where they became rows of knobs on an otherwise bald skull. The knobs have been explained as snails, and are sometimes portrayed that way.

As it was early in the day and I was still reasonably full of energy, I decided to bound up the hill and visit Buddha right away. In order to climb the hill to visit Buddha, I didn’t have to buy a ticket, but rather a meal, in the monks’ vegetarian restaurant. Meals were priced at $60-100HK, and I’d been advised to buy the deluxe.

I managed to reach the top without running out of breath, but I hadn’t counted on the climate. I’d dressed for the cold, misty morning I’d just left in Hong Kong, but here in the center of Lantau Island it was hot, sunny, and humid. By the time I got to the top of Buddha’s pinnacle I was

pouring with sweat, and the sweat didn’t stop running off me for, well, quite a while. The other tourists probably thought I was having a seizure.

Buddha’s bronze lotus flower sits atop a three-storey stepped-back concrete-and-steel structure that is, I suspect, a type of mandala, and which contains a museum mainly about the building of the Buddha. The mandala in turn is surrounded by fifteen-foot-high bronze statues of bodhisattvas kneeling and making graceful gestures toward the Buddha. Each bodhisattva offers a gift— a cup, a flower (gold, frankincense . . . ). Tourists have made a practice of tossing coins so as to land in these offerings, supposedly to bring luck or a blessing. There are signs asking them not to do this, but they do it anyway.

Buddha’s bronze lotus flower sits atop a three-storey stepped-back concrete-and-steel structure that is, I suspect, a type of mandala, and which contains a museum mainly about the building of the Buddha. The mandala in turn is surrounded by fifteen-foot-high bronze statues of bodhisattvas kneeling and making graceful gestures toward the Buddha. Each bodhisattva offers a gift— a cup, a flower (gold, frankincense . . . ). Tourists have made a practice of tossing coins so as to land in these offerings, supposedly to bring luck or a blessing. There are signs asking them not to do this, but they do it anyway.

Looking down from the Buddha I could see the temple buildings partly hidden by trees, their outlines obscured by vast rising clouds of incense. There were craggy, mist-haunted peaks, scarlet and saffron temple structures, parking lots, immeasurably tacky souvenir stands, gardens,

pavilions, galleries, and whole swarms of tourists.

I made my way down, and walked through a long shady garden toward the temple complex. It was here that I encountered my one and only monk, standing to be photographed with tourists. When I later mentioned to Erick that I’d only seen one monk in the whole monastery, he remarked that Sunday was probably their day off, and that they were very likely in Hong Kong visiting their families.

I found myself in a side gallery pasted with a large-character poster announcing “The Exhibition of the Secret Documents of the Buddhist Activities in Qing Palace, Part I.” I could hardly resist a title like this, so I went in for a recce. Unfortunately the poster was the only English in the exhibition, and the Secret Documents, being in Chinese, remained a Secret to me. There were books, manuscripts, and artworks on more or less Buddhist themes, some lovely, some less so.

I went in search of the restaurant, and my deluxe $100HK ticket procured me a place in a long, tasteful room decorated with long paintings on various traditional themes, not just Buddhist but also nature and animal paintings, and landscapes. The meal was amazingly good: if anything were to convert me to vegetarianism, it would be this. Grilled mushrooms were cunningly disguised, in form and texture, to resemble grilled beef. Something— I suspect tofu— was formed into the shape of prawns, along with realistic combination of pink and white coloring. All this with fresh, flavorful veggies, well presented.

I was getting famished for vegetables by this point. In China, if you order a meat or fish dish, what you get is a dish of meat or fish, with just enough vegetables, scallions or ginger or whatever, to give it flavor. If you order vegetables in China, what you usually get is stir-fried Chinese broccoli with hoisin sauce. In the States, Chinese food tends to have a much higher veg-to-meat ratio. Probably this has to do with the relative dangers of eating veg in the Third World: if your veggies aren’t cooked right, you get typhoid. Much better to eat meat, if you can afford it.

After a leisurely luncheon I made my way through massive clouds of incense to the temple itself: there are actually two, with a courtyard in between. The temple is garish inside and out with scarlet and gold, and features the only stained-glass windows I recall seeing in China. (The patterns were abstract, not ecclesiastical.) The main temple features three gold statues of Buddha ten feet high (Buddha Past, Buddha Present, Buddha Future [Maitreya]), with other, lesser, gold statues on other side. Altars were filled to overflowing with flowers and fruits. Huge scarlet banners proclaiming the Doctrine hung from the ceiling.

After a leisurely luncheon I made my way through massive clouds of incense to the temple itself: there are actually two, with a courtyard in between. The temple is garish inside and out with scarlet and gold, and features the only stained-glass windows I recall seeing in China. (The patterns were abstract, not ecclesiastical.) The main temple features three gold statues of Buddha ten feet high (Buddha Past, Buddha Present, Buddha Future [Maitreya]), with other, lesser, gold statues on other side. Altars were filled to overflowing with flowers and fruits. Huge scarlet banners proclaiming the Doctrine hung from the ceiling.

The temples were modern, the exterior filled with bas-relief in poured  concrete: dragons gaping down from the pillars while the walls themselves were filled with ranked arrays of celestial beings. (The older temple, I think, was behind, but closed to the public.) In the courtyard were large

concrete: dragons gaping down from the pillars while the walls themselves were filled with ranked arrays of celestial beings. (The older temple, I think, was behind, but closed to the public.) In the courtyard were large

electric light displays, sunbursty sorts of things on pillars. I don’t know whether they were permanent or just there for New Year’s, but they were the sorts of objects I could never imagine seeing at St. Peter’s Square, not even at Christmas. The whole in-your-face display was quite a

contrast to the more austere Western idea of religion that I absorbed at home. Not even the most gaudy baroque chapel compared to this.

I wandered around the temple complex for some time, trying to work out where the monks actually lived and did whatever it is that monks do. I found very little but banquet halls. Po Lin must do a landoffice business in banquets during the season. Given the quality of their kitchen, I’m not

surprised.

After another walk through the pleasant, spacious gardens I made my way to the nearby bus terminal and joined the long queue for Tung Chun. Rather than retrace my route to Silvermine Bay, I thought I’d take another way home and enjoy more of the island’s scenery. The way down the

mountain was just as spectacular as the way up, with additional views of the huge new airport at Chek Lap Kok, a nearby island greatly expanded and now host to the busiest airport in Asia.

Tung Chun was until recently a decaying village, but is growing up fast as a commuter island served by the Tung Chun Line, a subway that will take you very efficiently all the way to Hong Kong Island. It didn’t seem a worth a lot of time to investigate the new town of high-rises and shopping

malls, so I had an ice cream at Haagen Dazs, then made my way to the subway. (Kate later took me to task for my ice cream, telling me that Haagen Dazs was the highly expensive province of Hongkie nouveau riches, who only eat there because they can afford to. Just like in the States, in other words.)

That night I journeyed to Hong Kong with Erick and Kate to meet Erick’s friend Erik Todd, a computer-game guy whose current charge is The Sims Online, and who had flown in for a major electronic conference taking place the following weekend. Erik was accompanied by his “very expensive girlfriend” Anneke (her description, not mine), who is Dutch but who grew up partly in the States and speaks with an American accent. The two had just arrived after a long flight from the West Coast, but managed to perk up enough for dinner and a wander around Causeway Bay, where their hotel was located. Causeway Bay is a blazing monument to the power of consumerism, with neon displays towering up to the skies and looming over the narrow streets below, with music thundering out from narrow, brilliantly-lit stores that sell CDs and VCDs 24/7, and with all sorts of trendy shops and eateries.

Erik and Anneke crashed right after dinner, and who could blame them, but not before agreeing to join me on a side trip to Macau in a couple days. Erick and Kate and I wandered around for a while, enjoying the flabbergasting neon experience, before I descended into the underground and the long tunnel back to Mong Kok.

February 17

Monday started off with a failed shopping trip. I was trying to find something for Kathy, and ended up tramping over large sections of Wan Chai, Causeway Bay, and the Mid-Levels without finding the Perfect Something that I felt she deserved. Once again I was astonished at the profusion of street markets crammed between towering high-rise office and retail complexes, all very Bladerunner. Most of them were on the steep side streets that connected the main east-west thoroughfares. There were an amazing number of booths and stalls selling women’s clothing, some quite gorgeous, none of which would fit anyone of Occidental proportions. A pity, because Kathy would look very fine in a cheongsam

For lunch, because I was in a hurry, I went to my hotel’s dim sum restaurant for the worst dim sum experience of my life. The room was full of Chinese roistering over tables of wonderful-looking food, but I couldn’t get any of the help to so much as look at me. I suspect the waitresses had

no English and lacked the confidence to approach. Eventually an officious manager, with a very small amount of English, appeared at my table and took charge. I tried pointing at some of the gorgeous food sailing by on carts, but the manager would have none of this. “I would recommend

this, ” he snarled, and plopped in front of me a rack of pork in sesame sauce. With this I got the ubiquitous Chinese broccoli with hoisin sauce. The meal wasn’t bad, though there were a lot of bones in the pork, but I couldn’t help yearning for the beautiful dumplings I saw on nearby tables. For this I paid a vast amount, something like $17 US, with a single exception the most expensive meal I had in China.

Afterwards I gave a talk on plot and structure to Erick’s class at Hong Kong Polytechnic. These were a group of well-connected, savvy, high-tech geniuses destined for careers in cinema or computer games, and insanely hard-working besides. (They’re expected to complete their

MAs in a year, along with a major project— some of them are making a full-length motion picture filmed at Polytech’s own state-of-the-art digital studio.)

While they’re immensely savvy on every technical aspect of production, Erick told me that they lacked even the most basic understandings of how to structure a story, and so I gave them the basics, all the “rising action” and “falling action” and “resolution” stuff that most of you probably

learned in junior high, but that they’d never encountered. I tried to relate action to structured ideas of character. I used an episodic TV program as a template— because commercial TV forces a certain structure— and drew my little graph with its peaks and valleys, plotting dramatic tension against time. (They really perked up when I started on the graph— graphs they understand.) Then I related the whole thing to popular films, like “Titanic.” (They’ve all seen the Hollywood blockbusters.)

It all seemed to go well. Only one student fell asleep. Hardly anyone asked questions, but Erick tells me that’s normal.

I ended with a brief lecture on into mythology, because Erick ended up running a special class in mythology when he realized that his students hadn’t been exposed to any of it. Education over there is so relentlessly focused and contemporary that the students haven’t been exposed even to Chinese mythology, and probably their only connection to Homeric myth has been through “Hercules: the Incredible Journeys.”

Afterward we dined at the splendid Tai Woo seafood restaurant in Causeway Bay, with Erick and Kate and Erik and Anneke and yet another Eric, in this case Eric Snider, who designs games for the Palm Pilot, and his high-spirited, witty wife, whose name (to my embarrassment) I cannot recall. They were in town for the massive electronics convention taking place the following weekend. I began

getting used to the fact that everyone in the computer game business seemed to be named Eric. We developed ways of making it clear in company to which Eric we were referring— Erick Wujcik became “The Woodge,” Eric Snider became “Snideric,” and Erik Todd, so far as I know, remained “Erik Todd.”

Tai Woo has won multiple awards for its cuisine, and deservedly so. We ordered all the award-winning dishes and others that took our fancy, had a highly satisfactory meal, after which Erick and Kate joined me for a luscious ice cream dessert in the Cafe Eos, a Cantonese-Italian

restaurant where the food seemed sort of odd but the desserts divine. I walked through the colossal electronic onslaught of Causeway Bay back to the underground, Kowloon, and my hotel.

February 18

I’d made arrangements with Anneke and Erik to take a side trip to Macau. We met at the ferry terminal at 9:30 and bought our tickets. One of the annoyances of traveling to Macau is the necessity of clearing customs— I’m not sure why it’s necessary to get your passport stamped to travel from the Hong Kong SAR to the Macau SAR when they’re both

part of China these days, but I’m sure it helps the unemployment problem. People who regularly commute must have passports black with stamps.

The advantage of travel to Macau, however, is that once you’ve cleared customs you get to splurge in the duty-free shops, and you can buy duty-free on the ferry. I never did this, as I’ve never found duty-free shops to be a particular bargain.

The ferry was a hydrofoil and traveled with fine and easy rapidity, delivering us to the customs desk in Macau in about 50 minutes. The accommodations were closer to airlines than to a typical ferry, with assigned seats and lap belts. It was possible to buy meals and drinks.

Once we left the safety of customs, and had acquired the local currency (patacas), we were besieged by tour operators demanding that we take their tour. They left us alone only when we found a taxi and roared off to the Guia Fort and Lighthouse, built on a high point overlooking the harbor.

The old Portuguese fort, now in the midst of a spacious, attractive park that covers most of a plateau overlooking the city, provided excellent views of the city. Macau has the reputation of being Hong Kong’s slovenly, mildly retarded older brother, but that probably isn’t true

anymore. Our view provided examples of bustling economic activity in the forms of high-rise buildings going up on all sides, but (unlike Hong Kong) mercifully sparing the historic buildings in the city center. Some excellent

examples of colonial administrative architecture were visible from the fort, as well as views of the harbor. (Macau is a peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow, fortified neck, and thus nearly surrounded by water.) Macau isn’t as compulsively tidy as Hong Kong, but then nothing

is, except maybe Disneyland.

The Portuguese first glommed onto Macau in 1557, which makes it three hundred years older than Hong Kong. The name is a corruption of the Chinese A-Ma-Gau, meaning the Bay of A-Ma, the Goddess of the Sea (called Tin Hau in Hong Kong), whose story was related earlier and who ascended to Heaven from a spot on the southern end of the peninsula. The city was nominally Chinese until the local governor chucked out the last Chinese customs inspectors in the mid-19th century. In the 1970s the

Portuguese tried to give the city back to the Chinese, but the Chinese weren’t having it, and didn’t annex the peninsula until 1999, two years after they’d absorbed Hong Kong.

The city was attacked by a superior Dutch force in 1622, who paraded inland past the forts containing the despairing inhabitants, until a cannon shot fired by a Jesuit priest hit the Dutch powder supply. The resulting explosion badly confused the invaders, and the Jesuit rallied the Portuguese garrison and their Chinese auxiliaries and drove the Dutch

into the sea with much slaughter. The Dutch succeeded in seizing the East Indies and the Japan trade from the Portuguese around the same time, however, which made Macau a commercial backwater known for its poverty and vice. For a time it was known as the “island of women” from the number of prostitutes and child-slaves who were abandoned in the

town by their owners.

The old fort includes the chapel of Our Lady of Guia, which features a statue of the Virgin whose cloak miraculously repelled Dutch bullets during the invasion. The walls and ceiling have the remains of old frescos, Christian motifs executed in the Chinese style by local Chinese artists.

They are simple and charming, though what remains are only fragments of the whole.

We walked down through the park, and took the cable car to the city below, passing over a large analog clock set in the grass, presumably so that gods floating overhead will know what time it was.

From here we headed along hot, crowded, noisy streets to the Kun Iam Temple. The streets of Macau, unlike Hong Kong, are always loud with the annoying rattle of scooters and mopeds. Overhead was a spaghetteria of electric wire, a colossal city-wide tangle that any electrician would probably find horrifying.

On the way to Kun Iam’s temple we passed by the Lin Fong Miu, or Lotus Temple, which looked interesting but was closed. Due to the inexactitude of our map, we got somewhat lost on our way to visit Kun Iam, and wandered past a local Catholic school, with hundreds of Chinese students in neat uniforms, and past a cemetery, where cremated ashes reposed in lockers, each with a photo of the deceased and a little

vase for flowers.

Kun Iam is known in Hong Kong as Kun Yum, and elsewhere in China as Kuan Yin, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. (The Lotus Temple, a few streets away, is Kun Iam’s Taoist rival.) Kun Iam started out as the Indian Avalokiteshvara, one of Buddha’s more powerful manifestations, who was male, but underwent a sex change when he came to China. The

Chinese explanation for this is that mercy and compassion are female attributes, so Avalokiteshvara is best represented as female, but I suspect there was already a female goddess of mercy established in China when the Buddhists turned up, and she was promptly syncrecized into

Buddhism the way so many pagan traditions, like Christmas, ended up in Christianity.

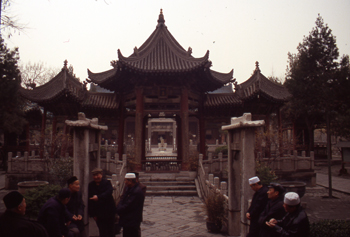

Kun Iam’s temple is about 400 years old, and is very large and ornate,  with formal gardens in the courtyard, full of beautiful old banyans, and a row of porcelain figures along the ridgepole of the roof. A constant cloud of sandalwood incense drifts from the courtyard toward Kunlun, the Western Paradise, where Kun Iam is said to hang out.

with formal gardens in the courtyard, full of beautiful old banyans, and a row of porcelain figures along the ridgepole of the roof. A constant cloud of sandalwood incense drifts from the courtyard toward Kunlun, the Western Paradise, where Kun Iam is said to hang out.

The Chinese tend to build their temples in threes, as I’ve remarked, and there are three outer temples under one roof that form a kind of gatehouse to the courtyard, after which a flight of steps takes you to the three altars of the main (central) temple. On the third altar is Kun Iam Herself, dressed in red as a Chinese bride. She is surrounded by

statues of the Eighteen Wise Men of China, one of whom— the one with round eyes and a pointed beard, on the far left— is none other than Marco Polo, who is said to have become a Buddhist on his visit to China.

Kun Iam is merciful and compassionate, as I’ve mentioned, and gives her followers many chances to become lucky. You can touch the little bonsai in the shape of the Chinese character for “long life,” or you can rotate the balls in the mouths of the stone lions three times to the left. (I did none of these things, as I didn’t know about any of this till after I left Macau.)

Feeling more than usually merciful on my way out of the temple, I gave some change to one of the beggar ladies sitting on the temple steps, and was immediately besieged by all the other beggar ladies, all demanding coins. I distributed all my change, but none of it was in the local currency, so I don’t know whether they were happy or not.

We headed to the center of town for lunch, where I had a lead on some Macanese cuisine. This was a long and hot march, longer and hotter than we intended, and I managed to get us lost at least twice, which Erik and Anneke took in good part. I have to compliment them on their tolerance for my vagaries. They are much more patient than I am.

On the way we passed by a number of old restored Colonial buildings, high-ceilinged buildings with tall pillared verandas and louvered French doors, painted in tropical colors, ochre yellows and greens.

We dined at the Restaurant Afonso III, highly recommended in my guidebook. The Chinese waitress spoke only Cantonese and Portuguese, and a couple of Portuguese businessmen at the next table had to interpret. I was hot and thirsty and bolted a liter or two of the local beer, which isn’t bad.

Macanese cuisine is a combination of Portuguese, Brazilian, African, Indian, and Cantonese. Afonso III turned out to be more Portuguese than not: I ordered a dish of lamb and potatoes in gravy, Anneke had a huge chunk of cod that appeared to be spiced India-style, and I seem to remember that Erik had fish as well. I ordered a huge plate of spicy

sausage as an appetizer and shared it. My lamb was very good and very European. Anneke didn’t care for her cod, but I suspect this was because she was Dutch and cod isn’t very interesting to a Dutch person. Erik was enthusiastic for whatever it was he ordered.

From this we got lost again on our way to the town’s main square, which was still filled with red lanterns, red pagodas, and other displays for the New Year. The brilliant New Year displays contrasted with the baroque Portuguese colonial buildings on all sides, and with the ornate Jesuit

From this we got lost again on our way to the town’s main square, which was still filled with red lanterns, red pagodas, and other displays for the New Year. The brilliant New Year displays contrasted with the baroque Portuguese colonial buildings on all sides, and with the ornate Jesuit

church. From here we wandered down Rua Sul do Mercado de

Sao Domingos through the Chinese market, lots of old traditional buildings, cut by narrow alleys festooned with webs of electric wire, featuring antique and trinket shops, where Mao buttons, old jade, and cheap brass buddhas compete for your attention in the stalls.

Few of the streets were on my map. Of course we got lost again, but this district was interesting enough so that this wasn’t very distressing. By and by we came out at the Jardim Luis de Camoes— that’s “Camoes” with a tilde over the o— which is a beautiful park with a fountain and old

banyans and gentlemen taking their pet birds for a walk.

From here we went to the old cathedral of Sao Paolo, which burned  down nearly 200 years ago. All that’s left is the facade, a single tall wall like a giant playing card jammed on top of the hill. The facade is an eerie baroque Jesuit monument covered with statues and reliefs meant to

down nearly 200 years ago. All that’s left is the facade, a single tall wall like a giant playing card jammed on top of the hill. The facade is an eerie baroque Jesuit monument covered with statues and reliefs meant to

illustrate Bible stories for the benefit of illiterate Chinese converts. There was Heaven, Hell, saints, devils, and of course the Savior, all of which looked even more alien after our walk through the Chinese mercado.

Tucked in a corner of the old cathedral complex, under the eaves of what would have been one of the back corners, was a tiny Chinese temple, a local god no doubt grinning at the misfortune of his mighty rival.

Looming above Sao Paolo was the huge Fortaleza del Monte, a massive stone fort still spiked with old cannon. Inside this is Macau’s museum, which I highly recommend. It’s one of the best historical museums I’ve ever seen, with nicely balanced displays on the history of Macau and its many cultures. The final display, no doubt installed since 1999, was a huge display on the history of the Chinese revolutionary flag, complete with patriotic music and an honor guard from the mainland. For the benefit of the soldiers I tried to look impressed.

After a refreshing snack we made our way down the mountain, then took a cab back to the ferry. By the time we got back to Hong Kong we were hungry again, and Erik and Anneke took me to an Indonesian restaurant near their hotel. Anneke, being Dutch, has a zest for Indonesian cooking, and this place was okay, though the bami didn’t seem right to me. We

found a much better Indonesian place later, near the lair of the Scots Guards Lady, of whom more anon.

February 19

The day opened with a great dim sum experience in Causeway Bay, with myself, Erick, Erik, Anneke, and newcomer Joe Williams, who had just arrived to participate in the electronics conference to be held that weekend. Apparently we’d reached our quota of Erics, and now we were collecting people named Williams. The lovely dumplings just kept on

coming, one course after another. I was particularly fond of the rice cooked in lotus leaves— grilled perhaps, since the rice had a nutty, charred flavor. Erick spent most of the breakfast trying to program the complimentary cellphone that the hotel had given Joe.

Afterwards I got to play tour guide to Erik and Anneke. They wanted to see the sights of Kowloon, and I needed to go to Tsim Sha Tsui to pick up my tickets for Xi’an, so I thought we’d go by the most scenic route available, the Star Ferry. Unfortunately once we got to Tsim Sha Tsui I managed to get thoroughly lost in the search for the travel agency,

and we probably wasted half an hour or more stomping around

hot, noisy streets, gazing at identical tourist traps and fending off scores of Pakistani tailors all salivating to make us new suits. It turned out we shouldn’t have taken the ferry to Tsim Sha Tsui, but to Hung Hom, where the ferry terminal empties out onto the square right where the NITS

agency has its offices.

Duh.

Once I got my tickets, we took the flyover to Hung Hom station, and the train to Mong Kok, where I was living in my hotel. We toured the Goldfish Market— which to that point I hadn’t seen in the daytime— as well as the Flower Market and the Bird Market. Unfortunately we were rather in haste, caused by my getting lost earlier, and getting lost a couple

more times with in blocks of my hotel didn’t help matters. We never did get to the Ladies’ Market (textiles, apparently).

After a quick return to my hotel for a shower and a change of clothes, I was off for an evening at the Happy Valley Racecourse, one of Hong Kong’s legendary sites. The electronics conference had rented a part of the Jockey Club and was putting on a buffet supper, and Erick had been nice enough to get me a ticket.

So now we had the whole gang: Erick, Kate, Eric, Erik, Anneke, Kelly, Joe, and Erick’s semi-nephew Zack. Problems developed early on, as Zack could pass for sixteen on a good day, but definitely not eighteen, which is the legal age for attending horseracing. Zack had to go home, and Erick with him as escort.

The rest of us had a jolly time, though, talking, enjoying the free food and liquor, and making the acquaintance of the locals. I met and chatted with several Chinese businessmen who will, I’m sure, be absolutely useless at advancing my career. I overheard a couple of Englishmen lamenting the

fact that nobody wants to be a race steward any more. The buffet was divided into Western and Chinese and Dessert. I concentrated on the Chinese and on the Dessert. I should also make note that it was the swank Happy Valley Jockey Club that produced the only meal in China that gave me a (fortunately minor) case of turista.

We had each been given a complimentary race ticket on entering. Mine were complete duds, of course, as I’m always unlucky at gambling. Kate was luckier, and probably made some money.

Our deluxe skybox didn’t give us a complete view of the track, there being a roof that obscured a corner of the raceway. We could have seen everything from the cheap seats. Since the Chinese are notorious for their addiction to gambling, and Happy Valley is one of the few places they

can indulge this tendency legally, I had been looking forward to seeing 20,000 locals going insane all at once, but we were so high up that the crowd was a rather distant abstract.

Horse racing, like baseball and cricket, is one of those sports from an earlier, more leisurely time. It has its own slow pace, with twenty or twenty-five minutes between each race, in which you have the time to amble down to the paddock and inspect the horses, or to call for another

bottle of champagne. I’m afraid that we of the video game generation got bored, and left before the last race, wandering out of the racecourse toward town to find a cab back to Causeway Bay.

Our taxi driver was both voluble and insane, and wished to communicate his geopolitical theories. His English wasn’t quite up to it, but he punctuated his points by using his hard little knuckles to punch the person next to him (in this case, me). I would have socked him back, but he was

driving at great speed through Hong Kong’s equally crazed traffic, and if I’d taken him out there would have been unfortunate consequences for all of us.

His theories, strongly flavored with geomancy, are difficult to reconstruct in retrospect, but he thought that America was great but that China would win in the long run, so long as certain temples remained standing. The Tin Hau temple featured heavily in this. He thought that Osama bin Laden