Pictures of Palau

The following is a description of a trip to the island republic of Palau taken in the spring of 2002. The journey required nearly 24 hours in planes and airports, but was well worth the trip.

(Text and images copyright 2002 by Walter Jon Williams, and may not be reproduced without permission.)

I’ve been looking through my slides from Palau, and getting a post-jetlag high just from looking at the pictures. Wow— I was there ! I did that !

Unfortunately most of the pictures sort of suck. The brand-new underwater camera I bought for the trip malfunctioned on its first try, advancing anywhere from 1-27 frames every time I took a picture, so some of the film rolls had only a few exposures. I replaced the camera with one I rented, an MX10, but it had a fairly steep learning curve. Underwater photography is pretty much by guess

unless it’s all automated, so I’d try to bracket the picture, taking one at f8, another at f11, another at f16, in hopes one would turn out okay— except that by the time of the second photo, the fish was usually half a mile away. And then it would take hours for the film to be developed— fortunately the SUN DANCER actually had a photo lab aboard— and by the time I saw the pictures I’d forget what

the settings were.

I snapped maybe 400 pictures, and if 150 turn out to actually have a recognizable image, I’ll be happy.

Digital is definitely the way to go for underwater photography. You know that the image you’re seeing in the viewfinder is the image you’re going to get. And I think

digital video is preferable to digital snapshots— there’s so much going on underwater that a still image doesn’t do it justice. Plus, you can just plug the camera into your TV set and get the images immediately, and you can edit on your

laptop. Some of the rigs the other divers had were amaaaaaazing— they’d made real movies, complete with titles and snappy editing and special effects and music.

All I need is some way to justify spending $3000 for a camera outfit I’d use only on my infrequent dive trips, maybe one week a year. (I don’t really care for video on the average terrestrial vacation.)

I think the only way to justify such a thing is another Hollywood sale, myself.

For such a remote place— halfway between the Philippines and Borneo— Palau’s 300-odd islands have a fair amount of history. The islands made contact with Europe in the late 18th century, and were annexed by the German Empire a century later. The Japanese replaced the Germans during World War I, and ran the islands until 1945, with the exception of Peleliu, which was captured by the US in a bloody, grinding, and totally unnecessary battle that resulted in 1200 US dead and 10,000 Japanese killed. (The civilians, fortunately, had been evacuated to another island.)

The Americans ran the islands from 1945 till the early 1990s, when theoretical independence was achieved, though the Palauans complain that the Americans are still really in charge.

The populations consists mostly of Polynesians, with an admixture of Melanesians and various Asians— mostly Filipinos, but also Chinese (mostly from Taiwan) and Japanese. The Polynesians are shorter than I expected, some very short indeed. They are a highly attractive people, very dark. Many of the women are droolable. The older men carry themselves with a formidable gravitas that is very impressive, though the younger men seem to have lost this knack.

Most of the native culture seems to have been lost, not so much suppressed as misplaced. The last of the distinctive long houses (bai) used for ceremonial purposes were destroyed in a typhoon about a hundred years ago, and the couple that now exist are modern re-creations. The local art form of the storyboard— a wooden bas-relief telling a local legend— is pretty much a modern creation dating from the work of a Japanese artist who lived on the islands in the 20s and 30s and organized the local artists into workshops. A few ceremonies having to do with pregnancy have survived, but I saw little evidence of anything else.

The local language has survived, and it’s very distinctive, the islands’ isolation having produced not so much a dialect as a language of its own.

Koror, the capital, sprawls over at least three islands. It’s worth an afternoon’s visit, but unfortunately I had four whole days there. The first day I marched around energetically in the tropical sun— Palau is only seven degrees north of the equator— and I pretty much saw all the sights, which consist of the official Palau museum, the unofficial Palau museum, and the Ben Franklin store. (The unofficial Palau museum, built with a local rich guy’s money, is far superior.)

On another day I went in search of the Japanese cemetery, which is said to have a Shinto temple attached, the largest outside Japan. Because no road is marked on Palau, and because the directions I had were no longer good— some of the landmarks had changed, apparently— I didn’t find the place, and by the time I realized this, I no longer gave a damn, I just marched back to my hotel and collapsed under the air conditioning for a few stunned hours.

There are a wide variety of restaurants— American, Japanese, Chinese, and even Italian. I didn’t encounter anything really wonderful, though the chow was all adequate.

Fortunately things improved mightily once I got on the dive boat. The boat had a capacity of 20 passengers (with ten crew), but only 14 were aboard, so I got a private cabin. The crew gave an interesting picture of the sorts of gypsies who make up the life.

The captain was a blond American. The cook, Yanis, was a young black woman from Belize, assisted by two young Filipinas. Of the professional divemasteers on board, we had Glenn from Newcastle, a Geordie who was constitutionally unable to end any sentence save with the query, ” . . . yah?” We had Allison from Nacogdoches. We had Thomas from Switzerland, though he’d learned to speak English in Australia apparently, and he spoke with an Aussie accent and referred to himself as a Swozzie. Then there were Marco and Bhoyet, the two Filipino dive professionals who spoke with Tagalog accents.

The resulting profusion of dialects was even more entertaining because they’d all started to parody one another’s accents, and everything had gotten so confused that Allison was ending her sentences with ” . . . yah?” and Glenn the Geordie was rolling his r’s like the Filipinos, and when he saw a picture he liked he’d say “verrrrry prrroffffesshional,” in a kind of falsetto the way the Tagalog speakers did. So it was very entertaining just listening to these folks, and before long the passengers were imitating the crew and the crew the passengers, and the conversations were very lively.

Relationships were, I guess, typical of those one encounters at sea. The captain had his fiancee on board— captains have their privileges. She was Australian, I think. Bhoyet had a wife and six children in the Philippines and saw them maybe once a year. Thomas had a fiancee in Australia and Allison had a sweetie who worked for another dive company, and they saw each other on her night off, which is Saturday. Glenn was married to a nice lady who lived ashore, and likewise saw her on Saturdays. Practically everyone was tattoo’d.

They were all pretty much young. You wonder where these people go when they’re older— the divers to dive shops on shore, I suppose, and the sailors to the merchant marine.

SUN DANCER II was a bit over 100 feet long and had three decks. The crew lived on the lowest deck, the passengers in the middle, and the upper deck had the kitchen, the dining room/lounge, and the open-air fantail bar, which featured the local Red Rooster beer on draft, amber, dark and mango-flavored. (Red Rooster is pretty good, by the way, and is probably the only Asian beer brewed according to the reinheitsgebrot, the German code for beer purity.)

Above the third deck was the open-air sun deck.

The bridge was forward of the passenger compartments, but while maneuvering through the islands the captain spent much of his time on the foredeck, running the ship through what looked like a Nintendo control pad. From the bridge he couldn’t get a good idea of the water depth, which is critical in a coral archipalego, where the depth can go very quickly from 90 feet to 3 feet— it helps to be right above the water where you can actually see the reefs. The charts, apparently, are useless, and he never navigates at night when he can help it.

Aboard SUN DANCER, the trains really ran on time. Somewhere between 6 and 6:30 each morning, one of the Filipina stewards brought the hot beverage of your choice to your door. Between 6:30 and 7 was a cold breakfast buffet, and then Yanis turned up at 7 to provide eggs and bacon for those who wanted it. At 7:30 was the first dive briefing, after which people drew on their wet suits and got into one of the two dive tenders (“Magic Bus” or “Magic Tram”— I myself was on the Bus) for the trip to the first dive site. After the dive, recovery, and return there was a hot snack usually in the pastry line, something like a 90-minute surface interval before the next dive briefing, and then the next trip out.

Then a two-hour break for lunch, another dive briefing, another dive, another snack with 90-minute surface interval, another dive briefing, another dive. Supper, and then a night dive, if there was one.

We were always diving on full, if not bulging, stomachs, which I didn’t care for, but the efficient schedules of the dive tenders didn’t allow for a lot of digestion time. (The SUN DANCER itself didn’t travel to the dive sites, since running aground was too great a danger. Instead the boat anchored in the vicinity of a number of sites and let the tenders do the ferrying.)

Another minor annoyance was the Photo Posse, divers so devoted to underwater photography that they’d commit any enormity in order to get the perfect shot. They’d body-check you, kick you in the face with their fins, and elbow you in an effort to claim exclusive rights to some particularly photogenic fish. At one point my dive buddy Mark asked me if I was a photographer. I said yes, and his face fell.

“Photographers don’t have friends,” he said.

“I’m not a photographer,” I corrected. “I just take pictures.”

Most of our gear stayed on the tenders for the entire trip. My mask, fins, weights, regulator, light, and BC (the Mae West-like device used for regulating buoyancy) stayed on the Magic Bus the whole time. Air cylinders were refilled on the tenders during the surface intervals. The only thing I carried on and off were my wet suit, camera, and wrist-mounted dive computer (and I only carried the computer around because I didn’t want to leave it lying around unsupervised). This was certainly trouble-free diving.

Palau is unique in the world in being on the crossroads of several different aquatic environments. It’s where the Philippine Sea meets the Pacific Ocean, and where the Philippine tectonic plate meets the Pacific Plate, which dives under the Philippine Plate in the Marianas Trench, a short distance away. Borneo is a brief sail to the south.

So what you get is fish and other fauna from all these environments. From the Philippines and Asia, from the central Pacific, from Borneo. They all drift in and start piling up in a startlingly wondrous profusion. Reef fish, corals, nudibrachs, dolphins, big palagic fish from the deep oceans. New species, either under or above the water, are discovered practically every week.

All those bodies of water muscling each other, combined with heavy tidal action, can create startlingly swift currents that have been known to sweep swimmers away at a fantastic rate. (Two divers lost at Peleliu were found eight miles away, within an hour.) So we were required to carry safety gear. We all had a Divers Alert, which is a kind of high-pitched whistle that attaches to your air supply. We all had an EPERB strapped to our gear (I’m not sure of the spelling here), which is a radio-location device that will alert satellites and Coast Guard and God knows what.

And we had the happily-named Safety Sausage, a four-foot-long bright yellow inflatable condom, which you blow up and hold upright, so that it stands above you like a little mast. I actually had to use this once, at Blue Corner, a famously tidally-ripped dive site, where I came up way the hell away from the dive tenders, with a couple other boats between us and them, and with a steep sea running that made me impossible to see unless I happened to be on top of a wave. Even with the cute little sausage flying o’erhead, it took them some minutes to see me.

Which brings me to the subject of:

CURRENT DIVES

The two famous sites for current are Blue Corner and Peleliu Wall, both wedge-shaped coral reefs extending out for some distance from islands, so that the tide can surve over them as well as around. Peleliu is particularly infamous, because it stands on the boundary between the Pacific and the Philippine Sea, and the current flies one way or another depending on which body of water is feeling more yeasty on any given day.

Blue Corner is famous for sharks. You drop down onto the reef at about 60 feet, and there use your “reef hook,” an implement developed on Palau, and which consists of a metal hook and a length of string that attaches to your dive gear. You place the hook on a piece of (hopefully dead) coral, play out the string, increase your buoyancy a bit, and fly in the “Superman position” over the reef while you watch the scenery. This means that you don’t have to waste any air fighting the current, and you can devote your full attention to what’s going on around you.

Blue Corner is famous for sharks. You drop down onto the reef at about 60 feet, and there use your “reef hook,” an implement developed on Palau, and which consists of a metal hook and a length of string that attaches to your dive gear. You place the hook on a piece of (hopefully dead) coral, play out the string, increase your buoyancy a bit, and fly in the “Superman position” over the reef while you watch the scenery. This means that you don’t have to waste any air fighting the current, and you can devote your full attention to what’s going on around you.

Because the upwelling current brings them food, packs of sharks cruise the reef almost continually. Sharks are shy of divers, usually, but if you’re not swimming, just floating there on the end of your line, the sharks will come up very close for an inspection. Sometimes dozens of them at a time, grey silhouettes in the great blue, floating echeloned in the distance like fighter squadrons.

These are black- and white-tipped reef sharks usually, in the 4-5 foot range, and they’re really not interested in chowing down on divers, so it’s perfectly safe, if a little unnerving, to let them cruise up to you. They really are perfectly designed streamlined machines, coldblooded mentally as well as biogically, with the dead, calculating eyes of a predator. Fortunately their dead eyes calculate people as “not food,” and they pass right on by.

Shark skin, by the way, is quite rough, like sandpaper. (I’ll spare you the trouble of touching it yourself.)

The sharks are also found on top of the reef, where they sleep. (The business about sharks having to swim all the time is a canard.) That is, they try to sleep, until packs of eager divers pounce on them in hopes of getting the perfect picture.

Other deep water predators turn up at Blue Corner as well: lots of jacks, yellowtail, sometimes tuna. They and the sharks cruise the wall together, apparently in the understanding that they’ll eat the smaller fish but not each other.

At Peleliu Wall we were prepared for anything. The dive briefing was: “if the current’s going this way we’ll drop here and fly over this way, if the current’s going the other way we’ll drop here and fly this way, unless something else is going on, in which case we’ll improvise and hope we don’t die.” Well actually they didn’t say “die.”

In the end, there was no current at all, everyone having worked their tide tables  right, and we moved along the wall without any trouble at all. Sharks, jacks, angelfish, butterfly fish, a couple spiny lobsters, some morays, and swarms of black parrotfish with weird twin-boom tails like television antennae.

right, and we moved along the wall without any trouble at all. Sharks, jacks, angelfish, butterfly fish, a couple spiny lobsters, some morays, and swarms of black parrotfish with weird twin-boom tails like television antennae.

Peleliu was some distance from where SUN DANCER was anchored, and so we spent our surface interval on the island. This was the site of a really stupid battle in World War II, occasioned when the Navy realized that MacArthur was about to get a lot of glory from invading the Philippines, and so decided to steal some headlines by invading Peleliu in order to “guard MacArthur’s flank,” which flank was not about to be attacked, but never mind.

MacArthur conquered much of the Philippines in the two and a half months it took for the Navy to secure the island. The Japanese were trying new tactics: instead of initiating a suicidal banzai charge against American machine guns and naval artillery, the Japanese dug in, and the Americans had to go into the caves after them. It was nasty, brutal warfare, as symbolized by the “thousand-man cave,” where 1000 Japanese died (and are still there, pretty much). Some of the Japanese didn’t surrender until 1948. And all for the sake of a few headlines for Nimitz.

The second Peleliu dive was in a modest current, and shallower, sloping water. It was probably the best single dive of the trip. We came down on a giant clam, a huge thing about five feet across. Giant clams are a feature of the area, but I hadn’t seen one so huge. I wasted a lot of film on them, because the fleshy parts of their bodies and lips are wildly colored, reds and purples and blues and greens, all mixed in psychedelic patterns, but when they saw (or felt) you coming they’d clam up, so you could never get the right picture.

The second Peleliu dive was in a modest current, and shallower, sloping water. It was probably the best single dive of the trip. We came down on a giant clam, a huge thing about five feet across. Giant clams are a feature of the area, but I hadn’t seen one so huge. I wasted a lot of film on them, because the fleshy parts of their bodies and lips are wildly colored, reds and purples and blues and greens, all mixed in psychedelic patterns, but when they saw (or felt) you coming they’d clam up, so you could never get the right picture.

The clam could, I suppose, grab a person, but since they’re bivalves and not meat-eaters I don’t know why they would. I rather imagine they’d spit you out before long.

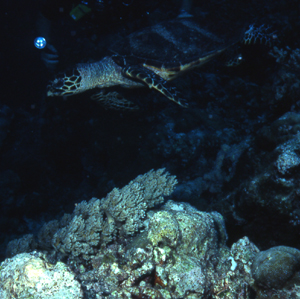

Along the way I encountered a couple green turtles, each about four feet long,  and followed them over many meters of ocean, snapping pictures as fast as my strobe would recharge (and followed by the Photo Posse, trying to body-check me out of their sight lines). Turtles are, I think, more bewildered than threatened by the attention they receive from divers, and only when you completely exhaust their patience do they swim away at the full speed of which they’re capable.

and followed them over many meters of ocean, snapping pictures as fast as my strobe would recharge (and followed by the Photo Posse, trying to body-check me out of their sight lines). Turtles are, I think, more bewildered than threatened by the attention they receive from divers, and only when you completely exhaust their patience do they swim away at the full speed of which they’re capable.

I had pursued one of the turtles down to 90 feet, and exhausted my air quicker than I’d planned. I did a slow ascend up the sandy slope, and then just as I was about to head for the surface I spotted a couple lion fish in a little cave.

Lion fish, like scorpion fish, are spectacularly barbed, spectacularly poisonous marine animals. Despite their formidable armament, lion fish are shy and tend to hide from divers, so it’s always an occasion when you can see one. These were about three inches long, though their feathered golden spines about tripled their size.

Happy with my discovery, I snapped a bunch of pictures and then tried to signal Mark, my dive buddy. Mark, a Brit, was very much a detail sort of chap and was closely studying coral. He liked to go over the reef inch by inch, perusing everything minutely, whereas I’m more of a big-picture sort of guy. This worked out well, actually, as the stuff that he missed was caught by me and vice versa.

Unfortunately he seemed immune to my gestures and I was fast running out of the 500 pounds of air that one likes to politely leave in one’s cylinder, so I had to ascend, and apologize to Mark later.

DIVING IN GENERAL

My diving experience can be related to the Howevermany Stages of Death, the ones that begin with Disbelief and progress through Bargaining and Anger to Acceptance.

Not that death was involved or anything. But my stages were, roughly, Annoyance, Frustration, Suitability, Harmony, Bliss, Disharmony, Annoyance, Anger, Bargaining, Acceptance, and finally Bliss.

Which is by way of saying that scuba diving is more complicated than Death. You need more equipment, for one thing.

And the equipment is always breaking, for another. Much of the training for the diver consists of learning what to do when the equipment, for which you have paid hundreds if not thousands of dollars, decides not to work.

Basically the ergonomics of diving suck. The equipment, though expensive, isn’t really very well designed for the human being, and there’s no motivation to make it so. If any gear company invests the money to rethink the ergonomics of diving, the others will simply copy the innovations and the investment will be lost.

During my dives I’ve had dive lights implode, knives fall off, masks flood, my air supply boil off into the blue, an infinite amount of gear getting tangled up with other gear, and my air supply detach itself from the mouthpiece and go on a voyage of its own. I have coped with all of these, usually with a reasonable amount of grace, but over the long haul it’s wearing.

I began my dives with two gear failures. My brand-new underwater camera malfunctioned, as detailed above, and my regulator, which had just been serviced, went free-flowing, which meant it was basically spitting out air into the blue more or less all the time.

I’d just had it serviced. (“Did you just have it serviced?” the cap’n asked me. “Whenever we get a free-flowing regulator, it’s always just been serviced.”)

The regulator couldn’t be fixed on board, as it would involve bodging a part. (“Bodge” and “air supply” are two phrases that should never be combined.) The crew was nice enough to give me one of their rental regulators free of charge. It was somewhat harder to breathe off of than my regular regulator, which may have been a cause of some of the other problems I encountered later.

Another problem I discovered early on was that I was underweighted. I used to carry this colossal amount of weight, 20 pounds, just to get me under the surface, but I hadn’t dived in a number of years, and during that time I’d lost a lot of pounds, so I didn’t know how much lead I’d need anymore. I assumed that since I’d lost a lot of buoyant fat, I’d need less.

Imagine my surprise to discover I needed =more.= During one dive, carrying 18 pounds, I had to invert myself during my safety stop and kick in order to stay at 15 feet. Not surprisingly I had to burn a lot of air just to stay down, and I kept running out early and having to come up. Losing weight had turned me into a highly buoyant bath tub toy.

Hence the initial Annoyance, Frustration parts of my cycle.

By the end of the first day, I was carrying 24 pounds of lead in the integrated pockets of my BC, and diving just fine. The fifth dive, at night, I used less air than anyone else. Suitability, Harmony, and subsequent Bliss resulted.

This went on till about midweek, at which point the profile abruptly changed, and in the middle of the day. I began consuming air a lot faster than anyone else in my group. I began to have to surface 5, 10, even 15 minutes ahead of everyone else. Disharmony, Annoyance, Anger! I was losing 20% of each dive.

Nothing like this had ever happened before.

I will spare you the strategies that I adopted to alter the situation (“Bargaining”) None of them worked. I was simply using more air, and I have no idea why. Possibly the borrowed regulator was a factor in all this.

Except at night, when I consumed air at the same rate as anyone else. Some kind of weird metabolic thing, I guess. (Note: my air consumption may have been related to an as-yet-undiagnosed case of acid reflux— I was inhaling stomach acid and impeding lung efficiency. —wjw)

Eventually I came to Acceptance of my lot— hell, I was still in dive paradise, even if had to come up early— and I achieved Bliss. All in all I did 21 dives for something like 18 hours under water, and this was good.

But I still can’t help feeling— considering the amount I spent on this trip— that Fate still owes me a five-hundred-dollar refund for the bottom time I missed.

WALL DIVES

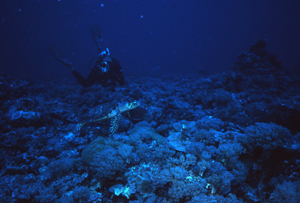

Mostly what we did was wall dives, floating along a wall of coral somewhere between 90-15 feet, just seeing what was living there. Most of these walls were along Ngemelis Island, which is pronounced “Nellie’s.” There are a large number of dive sites off Ngemelis, with names like Big Drop Off, Ngemelis Wall, Blue Holes, New Drop Off, and Fern’s Wall, plus the aforementioned Blue Corner off one end of the island.

Usually our highly skilled crew calculated the dives so that there would be little or no current, but the first dive at Ngemelis Wall was more exciting, with a furious tide tearing us along, hurling us up, down, and sometimes into the wall itself. (“Current’s really pumping, yah?” as Thomas put it in his Swozzie accent.) I found a turtle and tore along after it, the current itself carrying us faster than either of us could swim. I finally drove it into the Photo Posse, for which I felt a little sorry. Now the turtle knew what it was like to be a celebrity.

CAVE DIVES

The islands of Palau are coral islands, meaning they are made of limestone, a mineral famously susceptible to forming subterranean passages, tunnels, domes, underwater lakes, sinkholes, and caves. The islands are riddled with secrets, and divers are doing their best to ferret them out.

The islands of Palau are coral islands, meaning they are made of limestone, a mineral famously susceptible to forming subterranean passages, tunnels, domes, underwater lakes, sinkholes, and caves. The islands are riddled with secrets, and divers are doing their best to ferret them out.

We did several cave dives, beginning at Blue Holes, which are four holes atop the reef near Blue Corner, all of which join in a giant cavern that exits onto the wall somewhere between 70 and 90 feet. The cave itself was colossal and picturesque, though after you left it was just another wall dive. At the bottom of the cave was a monument to a group of Japanese divers who were killed there a few years ago. They dove the cave but were found outside, which suggests they may have surfaced from their cave dive only to be pounded to death against an iron shore. It’s hard to picture how this could have happened, or how there could have been no survivors of the party at all to explain how they died, and as a result the cavern has since born the alternate name “Temple of Doom.”

Our next cave was Siaes Corner, a dive site discovered by accident in recent years, when a lazy dive master, carrying tourists to another site, decided not to go the whole way and just threw the lot of them off his boat and onto that piece of reef. They came up raving about the terrific cave they’d seen. “Cave, uh, yeah,” the divemaster said. “Wasn’t it great?” and later went back with a buddy to put it on the charts.

The cave runs level along the reef at between 75-120 feet, and is about 120 feet long. The whole of SUN DANCER could have fit into it easily. I was on the tail end of the first group entering. Partway into the cave is a sort of “window” to the outside, and a group of sharks was patrolling outside. I thought this was a pretty could picture and began snapping away. The sharks apparently wondered what was flashing at them, and came in to investigate. Suddenly I experienced a rather lonely feeling, and hastened to catch up to my peers.

Besides the sharks, there were anemonies, lobster, and the usual array of colorful reef fish.

Returning from this dive the water suddenly burst into life with a pod of spinner dolphins, leaping all around us. Allie at the con put the Magic Bus into a wide circle, zooming around and around the dolphins, all of which kept leaping out of the water to say hello, or darting around the boat to play with us. It was one of those magic sunlight ocean moments (and I got no pictures, because I’d shot my last frame underwater).

In any case dolphins are really great for one’s morale. Spinners are smallish dolphins and as a consequence, I guess, live in and among islands and reefs.

The Magic Bus had to adhere to a rigid schedule, and eventually we had to leave the dolphins behind. As the spinners fell astern they justified their name by leaping high out of the water, spinning like tops winking in the sun in order to get a view of us and find out what had happened to their new friends.

The next cave dive was at Chandelier Caves, which is right in Koror harbor. While Blue Holes and Siaes were just huge rooms, Chandelier was what I think of as a proper cave, with stalactites, stalagmites, rooms, and tunnels. There are four rooms altogether, each of diminishing size, all with an airy dome stretching up above the surface of the water, and each connected to the last by an underwater tunnel. The first room has the “chandelier,” the huge tawny formation descending from the ceiling.

The next cave dive was at Chandelier Caves, which is right in Koror harbor. While Blue Holes and Siaes were just huge rooms, Chandelier was what I think of as a proper cave, with stalactites, stalagmites, rooms, and tunnels. There are four rooms altogether, each of diminishing size, all with an airy dome stretching up above the surface of the water, and each connected to the last by an underwater tunnel. The first room has the “chandelier,” the huge tawny formation descending from the ceiling.

We surfaced in each chamber in turn. The photography was spectacular, with the surface of the water reflecting either the stalagmites pointing up or the stalactites pointing down (depending on whether you were above or below the water yourself). The air in the caves was perfectly breathable, and it was a modest thrill to float in each chamber, conversing while the wavelets caught the powerful light of the dive lights and reflected it shimmering up on the ceiling.

Somewhere between the second and third chambers I got briefly lost, totally disoriented. I couldn’t tell what was up or down, or where my friends were, and all this despite the fact we were in a smallish place with nowhere to get lost =to,= if you see what I mean. When I gained my bearings I realized I’d pushed on too far, and was in the passage between the third chamber and the fourth. When I backtracked I found my group, as well as the realization of how disorienting cave dives can be, and why so many get lost and are never seen again.

The fourth chamber is small and rather resembles a large spa, with rocks to sit on. Supposedly the local professional divers celebrated the Millennium here, with a party.

For once you had to feel that the champagne would have been superfluous.

NIGHT DIVES

We did at least three night dives, and I suspect there was a fourth I failed to record.

We did at least three night dives, and I suspect there was a fourth I failed to record.

Night dives are particularly magical, with the reef asleep, and the divers hovering with their lights like Spielberg aliens. At night the reef is inhabited by different animals: octopoids, and squid, nudibranchs, crabs, shrimp, eels, and cuttlefish. In the dive lights they all show their brilliant natural colors, which are washed out in the day,.

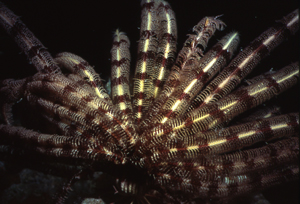

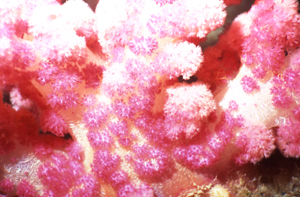

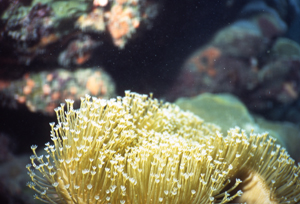

The soft corals are brilliant blood-red or flaming purple. Starfish blaze with every conceivable color. Many of the hard corals look furry, as night is when the coral polyps come out to feed. Tiny little shrimps gaze back at you with phosphorescent eyes. One reef that we dived was covered with brilliant scarlet nudibranchs,  almost perfectly circular, that you could only tell were animals because of the horns at one end. Other nudibranchs are striped in blazing colors, and had scalloped shapes.

almost perfectly circular, that you could only tell were animals because of the horns at one end. Other nudibranchs are striped in blazing colors, and had scalloped shapes.

(What is a nudibranch, you ask? Hard to say. If you called them slugs it would call the wrong picture to mind. Most of them are a lot flatter than terrestrial slugs, and ovoid or circular, and they can sort of swim with an undulating motion, like a tea towel flung on the wind.)

My dive buddy Mark’s approach, gazing minutely at the reef, was the perfect tactic to take with night dives. So many of the things you see are small, living on or in the corals. So many things are seen by accident, just by hovering around. One night, at the very end of the dive, he found a lion fish, brilliant red-gold and covered with feathered poison barbs, lying in a sheltered alcove.

My dive buddy Mark’s approach, gazing minutely at the reef, was the perfect tactic to take with night dives. So many of the things you see are small, living on or in the corals. So many things are seen by accident, just by hovering around. One night, at the very end of the dive, he found a lion fish, brilliant red-gold and covered with feathered poison barbs, lying in a sheltered alcove.

When you rise from a night dive the stars blaze above you with perfect diamond brilliance, and you rise and fall to the warm scend of the waves, and when you wave a hand in the water it trails gold or green phosphorescence. It is the most perfectly peaceful thing you can imagine.

Then you return to the boat, and the captain hands you hot cocoa and a warm fuzzy towel, and the peace of the night follows you to bed and to your dreams.

ROCK ISLANDS

The unimaginatively-named Rock Islands are completely unique in the world. They have names in the native language, but even these are depressingly mundane in translation: “the little island across the channel from the bumpy island,” etc.

A group of 400 small islands near Koror, the soft limestone Rock Islands were undercut by tide and bacterial action so that they now overhang the sea. Many of them look like mushrooms— and big green pointy tropical mushrooms, at that. They’re riddled with passages, caves, and hidden bodies of water— over 70 lakes, each with a unique ecosystem— and covered with abundant tropical growth. Banyan trees standing on their tangle of giant roots, ironwood, heliotrope, coconut palms, fig trees, and the carnivorous pitcher plant with its bowls of sweet nectar to lure its insect prey. The islands host the medicine tree as well as the poison tree, with its highly allergenic black sap.

Overhead I saw (and heard!) white cockatoo, kingfishers, and the white tropic bird with its long, elegant tail. Fruit bats were also a fairly common sight— very large, they could be seen frequently in the daytime though they feed only at night. There are also salt-water crocodiles, which are quite shy and which I never observed.

Cap’n Scott took SUN DANCER on a twisting tour of the Rock Islands, flying through narrow passages fringed with reefs— deep blue for safe water, turquoise for shallow reefs, green for the islands, all a glorious feast for the eyes. We ended at the Arch, a natural arch that formed one of nature’s own Kodak moments.

Cap’n Scott took SUN DANCER on a twisting tour of the Rock Islands, flying through narrow passages fringed with reefs— deep blue for safe water, turquoise for shallow reefs, green for the islands, all a glorious feast for the eyes. We ended at the Arch, a natural arch that formed one of nature’s own Kodak moments.

We then embarked on the tenders for a visit to some snorkel sites, followed by a  swim through a partially-submerged tunnel into a hidden saltwater lake. The lake was a home to a lot of giant clams, some very large coral formations, and brilliantly-colored soft coral. There was an almost solemn sense of quiet and isolation in the silent pool surrounded by long shadows and the steep jungle growth. After which we returned from this warm tropical womb, down the tunnel to sea and civilization.

swim through a partially-submerged tunnel into a hidden saltwater lake. The lake was a home to a lot of giant clams, some very large coral formations, and brilliantly-colored soft coral. There was an almost solemn sense of quiet and isolation in the silent pool surrounded by long shadows and the steep jungle growth. After which we returned from this warm tropical womb, down the tunnel to sea and civilization.

JELLYFISH LAKE

JELLYFISH LAKE

I’m almost getting tired of writing “unique in all the world,” but that is a term that clearly applies to Jellyfish Lake. A completely isolated lake in one of the Rock Islands, the island is home to about 10,000,000 jellyfish and very little else.

The jellyfish entered the lake in the dim geologic past, when the level of the sea  was higher than it is now. When the ocean receded, the jellyfish were trapped, and rapidly exhausted the food supply. The jellyfish mastigias sp. urvived by turning from hunting and gathering to farming.

was higher than it is now. When the ocean receded, the jellyfish were trapped, and rapidly exhausted the food supply. The jellyfish mastigias sp. urvived by turning from hunting and gathering to farming.

They’ve lost the ability to sting (mostly), and instead have developed a symbiotic relationship with algae that live in their bodies. These algae produce the sugars on which the jellyfish live, and the jellyfish protect the algae from anything that might want to eat them.

At night, the jellyfish descend to a lower toxic level of the lake. Below 15 meters the lake is poisoned by hydrogen sulfide— if you dive that far you will shortly die, as the sulfide will enter through your skin and kill you. The algae in the jellyfish, however, use this layer as fertilizer for their internal gardens. At sunrise, the jellyfish pulse their way to the surface and, as the hours go by, follow the sun across the lake in one vast swarm.

At night, the jellyfish descend to a lower toxic level of the lake. Below 15 meters the lake is poisoned by hydrogen sulfide— if you dive that far you will shortly die, as the sulfide will enter through your skin and kill you. The algae in the jellyfish, however, use this layer as fertilizer for their internal gardens. At sunrise, the jellyfish pulse their way to the surface and, as the hours go by, follow the sun across the lake in one vast swarm.

The jellyfish almost died out in the last El Niño year, when the water temperature got too high. But they’re back in larger numbers than ever, more than three times the earlier estimate.

The jellyfish almost died out in the last El Niño year, when the water temperature got too high. But they’re back in larger numbers than ever, more than three times the earlier estimate.

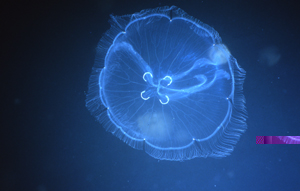

The jellies range anywhere from tiny to dinner-plate-size, and feature a pulsing dome and a shortish, thick clumps of tail. They’re a golden-brown in color, the color of the algae that inhabit them.

Also present in the lake are white moon jellies, which live off microscopic crustaceans. A few species of fish and some anemones also coexist with the jellies.

Also present in the lake are white moon jellies, which live off microscopic crustaceans. A few species of fish and some anemones also coexist with the jellies.

It’s a steep walk uphill and then down to reach the lake, past a few examples of the nasty poison tree. There’s a small pier there, and when I visited it was full of Japanese tourists, so rather than change into my gear I just grabbed mask, snorkel, flippers, and camera and jumped in.

I saw the first jellyfish after a few minutes— large ones, pulsing away— and continued until the jellies began to thicken. The strange feeling of soft jellies bumping up against my skin is difficult to capture in words— it wasn’t erotic in any way, but it was sensual in the same way that an erotic touch is sensual. In the center of the lake they were so thick it was like soup, and the touch on my skin almost continuous. You felt as if you could practically stand on them.

It’s difficult to express the magic of it, particularly as the word “jellyfish” is going to creep out half the readers of this note. Some people =were= creeped out. But I found it glorious, and I regretted that the sun began to descend, and it was time to make the difficult, steep hike back to the sea.

THE MATTER OF MANTAS

One of the things that attracted me to Palau in the first place was the chance of seeing manta rays, and lots of them. These magnificent creatures are known to haunt the German Channel, a natural passage through the reef, where the incoming tide brings them lots of microscopic creatures to scoop up and eat. Whole packs of mantas have been known to hover in the channel for ages, doing barrel-rolls to stay in place. I badly wanted to see this.

Unfortunately the cap’n either misread the tide table or suffered from a galloping sense of optimism, because we ended up in the German Channel on the outgoing tide, and there wasn’t much in the water but sand. A couple of the other divers caught a glimpse of mantas galloping one way or another along the channel, visible for only a few seconds, but I saw squat.

I did see one manta, briefly, but from the boat. It was breathtaking even so, and I grabbed my mask and snorkel and leaped into the water . . . but by then the critter had flown away.

There was only one dive that I decided to skip, being tired that afternoon, and that was the one where the divers saw mantas. I didn’t dare skip a dive after that, but my manta luck had run out.

I remain deeply pissed off about it, too.

MANDARIN FISH LAKE

Mandarin Fish Lake is a small salt water lake in one of the Rock Islands, connected to the sea by a winding channel. It is the abode of— big surprise— mandarin fish, which are small, brightly colored, highly aggressive fighting fish, in coloration, behavior, and temperament very like hummingbirds.

Mandarin fish live in broken, dead coral, and hide during the daytime, coming out only at dawn and dusk to fight and fornicate. (We went at sunset) The females are a couple inches long, the males 3-4 inches, and they are brilliantly colored, scarlet, blue, and green. Their pectoral fins are in constant motion, like a hummingbird’s wings, and they can hover or fly backwards just like a hummingbird.

Mandarin fish live in broken, dead coral, and hide during the daytime, coming out only at dawn and dusk to fight and fornicate. (We went at sunset) The females are a couple inches long, the males 3-4 inches, and they are brilliantly colored, scarlet, blue, and green. Their pectoral fins are in constant motion, like a hummingbird’s wings, and they can hover or fly backwards just like a hummingbird.

They are very fast and very shy, so the best way to get a glimpse of them is to hover motionlessly nearby, pretending to be, say, a lump of coral (assuming a lump of coral could float, that is). I hovered over some coral for ten minutes, waiting for a critter I could barely observe to come out, and in the end discovered it was a goby. Very annoying.

I subsequently found a better chunk of dead coral that had dozens of the brilliant little critters living in it. After a while they got used to me and began flying around, though they stayed close to cover, and they all vanished if I made so much as a micro-movement. The males fought each other (briefly) and pursued the females (who generally vanished pretty quick.) I managed a couple off-center photographs— the targets would vamoose well before I could aim the camera— but for the most part I just watched them in delighted fascination.

If only you could put a mandarin fish feeder in the back yard . . .

DOLPHIN PACIFIC

Dolphins, as I remarked earlier, are good for the morale.

Accordingly I laid out some extra $$$ for the chance to dive with dolphins at Dolphin Pacific, a brand-new facility across the bay from Koror. This facility was, I was told, built by the chairman of Sony (whether Morita or some other chairman I don’t know), whose disabled children or grandchildren were aided by Dolphin Therapy.

Right! Dolphins can heal! Imagine my surprise! Apparently disabled and/or autistic children show improvement after being lowered into the water with dolphins. Maybe it’s due to Healing Sonic Rays, or just the dolphins’ cheerful, goofy presence. They certainly made me feel better.

The facility is large and first-class, with floating wooden walkways connecting dolphin pens of netting. It is in fact the largest dolphin research facility in the world, and they do genuine research there. The dolphins could easily leap from one pen to another, or for that matter leap to freedom, but for some reason they don’t. And even though we saw some tasty squid, and a school of mackerel living in one of the pens, the dolphins have given up hunting, and live entirely on what their keepers give them.

The keepers hope to take the dolphins to sea one of these days, and hope to lead them back to their pens at the end of the trip.

The dolphins are Pacific dolphins, larger and longer than the spinner dolphins we’d played with earlier, and were rescued from Japanese fisherman at the going rate of nine dollars per pound. Maybe they’re just happy to stay where they’re not going to be eaten.

You couldn’t just jump into the water with the dolphins, you had to be introduced first. One of the hostesses would take you into the water with the dolphins and show you how to touch them, how to feed them, and how not to alarm them. There were a couple classes of schoolkids there going through the same intro, one group Japanese, and I wondered if they’d flown all the way to Japan for this. (The children seemed alternately fascinated and terrified of the dolphins— and part of me wondered why parents seemed so insistent on introducing their toddlers to 800-pound carnivores. The other part thought it was fine, though.)

You couldn’t just jump into the water with the dolphins, you had to be introduced first. One of the hostesses would take you into the water with the dolphins and show you how to touch them, how to feed them, and how not to alarm them. There were a couple classes of schoolkids there going through the same intro, one group Japanese, and I wondered if they’d flown all the way to Japan for this. (The children seemed alternately fascinated and terrified of the dolphins— and part of me wondered why parents seemed so insistent on introducing their toddlers to 800-pound carnivores. The other part thought it was fine, though.)

There were also automated platforms that could lower wheelchair-bound kids into the water for the same experience.

During the course of the afternoon I found out that dolphins adore me. They would follow me as I walked around their enclosures, make conversation, and ask to be petted. (Petting them was forbidden but I did so anyway, as it seemed the polite thing to do.) When I left they would leap high into the air to see where I’d gone.

They didn’t act this way for any of the other divers, or for the staff. I continue to feel smug about this.

Maybe they knew I was the author of “Surfacing.”

When the three of us put on our gear and descended into the deep enclosure, we sat in a circle with a couple of the keepers. We’d been taught the sign for “come here,” which involved placing the (for argument’s sake) right hand palm-out with the left hand on the right biceps. The dolphin would swim up, put his bottle nose in your hand, and pirouette.

Did I mention dolphins are very good for morale?

The dolphins were heavily scarred, apparently from fights among themselves. They heal quickly though, and showed no ill effects. To the touch they feel like a wet inner tube, except for their teeth, which are very, very sharp. (We were encouraged to put our hands in their mouths, and apparently no tourists have yet lost fingers.)

Dolphins seem to make three kinds of sounds. There is a high whining sound, a low kind of murmling noise, and the farting sound they make with their blowholes (and apparently for the same reasons humans make farting sounds: to indicate disgust and/or mean amusement).

We fed the dolphins. And took pictures of the dolphins. And had the dolphins spin on our palms. We watched the dolphins leap up out of the water, and plunge back down in a flurry of bubbles. We stroked the dolphins.

Dolphins are good for the morale. I felt Therapized. And I think the dolphins had a good time, too.

KAYAKING THE ROCK ISLANDS

My last day in Palau I was feeling pretty bored with Koror, so I scheduled a kayaking trip in the Rock Islands. I’d never been in a kayak before, but I’m reasonably at home on water craft, and I anticipated little trouble. Nor was there any.

There were four of us plus a guide. There was more snorkeling involved than actual paddling from one place to another, and I would recommend the snorkeling to anyone who hadn’t just spent 20 hours under water. (It suffers by comparison.) I did manage to see a fish I hadn’t seen before, a juvenile harlequin sweetlips. (I am cheered by the fact that I share a universe with something called a “juvenile harlequin sweetlips.”) It’s a smallish fish, black with white spots, with its pectoral and dorsal fins forming a kind of floating, swirling skirt, like a tutu. When it grows up the spots turn into stripes and it morphs into a very different-looking fish indeed.

Our trip was made somewhat less interesting by an expedition to the German lighthouse, which was built in colonial times atop one of the Rock Islands near the channel that leads to Koror. There was a 45-minute walk uphill to the top, then another walk down. The view from the top of the lighthouse (which is now used as a base for a radio antenna) is nice, but it isn’t worth the time. The walks took particularly long in our case due to an older woman in the party who required more attention.

Along the way we passed some Japanese installations from the Second World War. There were two gun batteries that held some long cannon, five or six-inchers,that seemed of an elderly design even for WWII, and had possibly been taken off an old ship and mounted there. The guns had been pretty comprehensively destroyed by American engineers after the war, the breeches blown with, I guess, TNT.

We also passed the stone platform for a Japanese camp, which had been built by Palauan and Korean forced labor during the war. Since the platform was built by slaves, size was no object, and it was rather substantial, still looming over the trail.

There were also a couple caves where the Japanese had stored ammunition. The caves seemed some distance from the batteries, and I was picturing frantic gun crews running like mad up and down the steep trail with six-inch shells on their shoulders.

Fortunately for everyone concerned, the Americans never invaded here and the guns were never fired in anger.

One of the caves featured a lot of wildlife, a ceiling filled with cave crickets. These are blind insects with long, long feelers that leave the cave at night to hunt. Our guide flicked a number of these off the ceiling at our lady tourist, but she declined to freak. I was glad she didn’t, as I didn’t want her to bang her head on the ceiling in surprise.

The views of the Rock Islands were spectacular, and I wish we’d spent more time cruising their blue lagoons than tramping uphill in the jungle. The profusion of tropical growth on the islands was wonderful, as was the bird life. We even saw some petroglyphs carved onto a rock ledge thirty or so feet above the water, but one of these featured a horse, which argues against their being of great antiquity.

I was headachy and out of sorts by the time we returned, but this wasn’t anybody’s fault. I took a cooling shower and got a ride back to the hotel, where air conditioning awaited. While resting, I watched the Winter Olympics on television. It seemed quite another world.

The return flight to the States left at about 2am (Continental Airlines’ monopoly on so many Pacific routes means their flight times don’t have to be convenient to anyone.) The plane was packed with locals, most of whom were accompanying huge foam coolers, and who were being shepherded by one older man who wandered through all the chaos with the quiet dignity common in many of the older Palauans. My guess is that the coolers were packed full of fish, to be purchased on Guam by Japanese, and soon destined for the sushi stands of Tokyo and Kyoto.

So the glorious journey to Palau came to an end, as all must, with another 24 hours in airports and crowded steel tubes. Quite a contrast from the glories of the Rock Islands and the reefs— but then, I suppose, that’s the point.