A few days ago I had a visit from my cousin Cindy, who was in transit from Minnesota to visit friends in Arizona. Cindy has been assembling a genealogy of our family, and I was able to share a few stories about our history, including the story of how I became a Williams.

I figure I may as well share it with the rest of you.

My paternal grandfather Victor Kuusikoski (born 1876) hailed from the town of Kankaanpää, which was then in the Finnish province of Ostrobothnia, a part of the Russian Empire. Kuusikoski either means “Seven Pines” or “Seven Rapids,” or so I am told— the Finns in that part of the world usually chose a name from their environment, and if they moved they often changed their name to match their new neighborhood. (And frequent name changes also might have kept them safer from the Russian military draft.)

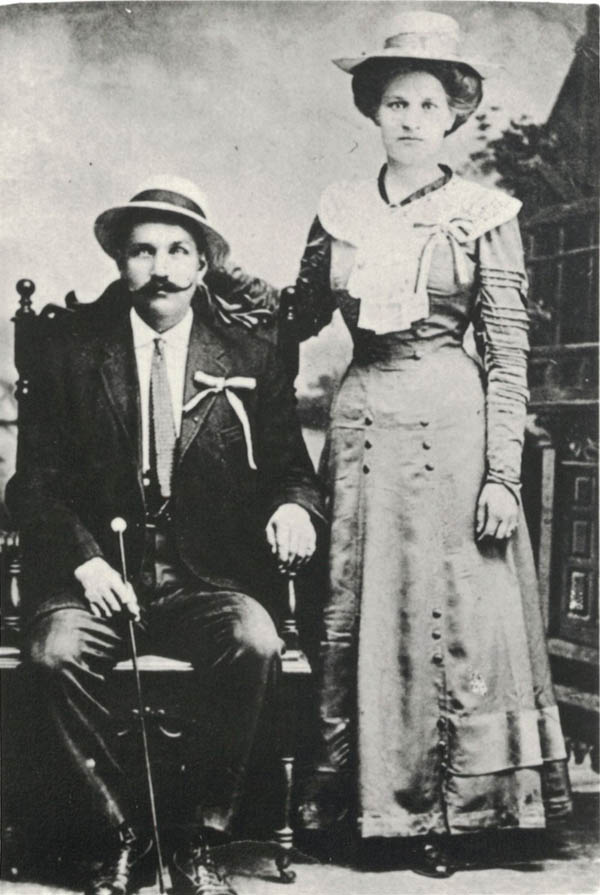

Victor married Alexsandra (born 1882) , whose surname I have as Myllymäki but Cindy has as Myllyharju— I believe they both mean “Mill Hill”— and any confusion is not made any clearer by her brother Anton, who used the name Anttila. They had a daughter named Josephine (Cindy’s grandma) before Victor had pretty much had it with Ostrobothnia, or the Russians, or both. The plan was for him to head into the New World and establish himself, after which he would send for Alexsandra and their child.

The plan went awry pretty quickly, as Victor ended up in a lumber camp in Canada, where he worked as a lumberjack. This was a “hot bed” outfit, where Victor had use of a bed for a 12 hour shift, and someone else the other 12 hours. On Saturdays the lumberjacks were transported to the nearest town, where they could spend their pay in company-owned stores, saloons, and brothels.

This system was designed to trap the workers, and Victor was stuck in the trap for about eight years. When he emerged, he had a new name.

The boss of the camp was Welsh. (Welsh people were known as “Cousin Jacks,” though the dictionary tells me the term is used for Cornishmen. Some people can’t tell one Celt from another.) When Victor arrived at the camp, the boss asked his name. He then asked how the name was spelled.

“From now on your name is Williams,” said Cousin Jack, making him an honorary Welshman. Victor was therefore able to give his surname as Williams when he eventually moved to the States.

But in the meantime, Alexsandra had got tired of waiting for her husband to send for her, and got on a steamer to New York on her own, where she established herself as a cook for rich people. Once she got herself settled, she sent for daughter Josephine, who came to America on her own.

Josie was 10 years old when she made her journey. Let it not be said that Finns are without resource.

At some point Victor made a not-quite-legal visit to the States, to check out the availability of farmland. Apparently the trip had positive results.

Victor engaged in a correspondence with Alexsandra, trying to convince her to join him at his farm, or at any rate the farm he intended to buy. She had built a life for herself and her daughter, and was reluctant to give all that up, but eventually she joined Victor in Minnesota, in a largely Finnish district. Three sons followed, the last of whom was my father.

The last time I visited Victor and Alexsandra was when I visited their grave in 2018. They are in the cemetery of Markham Township, after which I named the nautical family in my Privateer series. The gravestone proclaims them WILLIAMS, which looks a little odd next to the Wirtanens, Kilpelas, and Kaupinnens buried alongside them.

As a tribute to my far-traveled grandfather, I put a character named Victor Kuusikoski into a couple of the Privateer books, as an immigrant sailor persecuted as a witch. There is in fact witchcraft in my family, but my grandfather wasn’t the magic one. Maybe I’ll tell that story another time.

Walter, I really enjoy these little family history vignettes you share. It’s fascinating to see the paths traveled by immigrants and that there is more adventure in most of our family backstories than we imagine.

Hi Walter—Alexsandra and Josephine (named for the empress?) would seem to embody the Finnish quality of “sisu”!

As an immigrant, albeit one who has not had to endure such dire straits, I too find your family histories fascinating. Thank you for sharing them.

Speaking of Finns in your novels, I believe you mentioned on our chat that Paavo Kuusinen wasn’t an auctorial cameo (like Roger the guard at Castle Amber!). However, was the name an homage to the Olympic cyclist, or a relative/friend perhaps?

Hey Derek,

Yeah, that generation (and the one that followed) were just brimming with sisu.

What I wanted with Paavo Kuusinen was a character that the reader would remember from one book to the next, and giving him a very, very distinctive name was a part of that.

Kuusi means six and pine in Finnish, koski means rapids. So Kuusikoski would mean either Six Rapids or Pine Rapids. My guess is the latter.

Thank you for sharing the story behind your lastname!

Kuusi is actually spruce. So Kuusikoski would be Spruce Rapids. Pine is mänty in Finnish.

Pekka, thank you. I grew up thinking kuusi was six, but then someone rather forcefully corrected me and told me it was seven. So I was right all along, tra-la!

Comments on this entry are closed.