After three nights on the Costa del Sol, it was time to hit the breakfast buffet and ship out to view the wonders of Granada.

A note of appreciation for Spanish hotel breakfast buffets. There’s fresh fruit, croissants, chocolate croissants, lots of crunchy and non-crunchy breads, juices, and a myriad of pork products like Serrano ham, chorizo, various sorts of salamis and other sausages. Most have the rather dismal chafing dishes of scrambled eggs familiar from American hotels, but there are often hard-boiled eggs or omelettes to order, and sometimes you get lucky with eggs poached in olive oil, which are beyond delicious.

The Spaniards like their coffee the same way Americans do— weak and with far too much milk. I had to drink a lot of this coffee to reach my standard level of awareness. The breakfast buffets usually deliver coffees from machines, so you can order “cappuccinos” or “lattes” composed of 90% foam. My trick was to order an Americano and a cappuccino and transfer the foam from the latter onto the former.

Once in Granada we went straight to the Alhambra without passing “Go.” In the not-too-distant past, all the tickets to the Alhambra were bought by scalpers, so visitors paid through the nose. Now they have a system in which all tickets are printed with the passport number of the purchaser, and you have to show your passport and the ticket to gain entrance. Good move! If only they did this at theaters and concerts.

Granada has a history unique in Spain and possibly the world. It was the last Moorish kingdom in Iberia, but when the Moors arrived the town was Jewish, and for a couple centuries the culture was mostly Sephardic, with a token Moorish leader who paid a lot of attention to the instructions given him by his Jewish vizier. This arrangement ended in 1066, when the Muslim ruler was poisoned along with his son, and the vizier was blamed. Thousands of Jews were killed, and the vizier Joseph crucified.

In 1228 the Nasrid Dynasty was established, and it lasted until 1492, when the last king Muhammad XII, for some reason known in the West as “Boabdil,” surrendered without a battle to Ferdinand and Isabella. The Catholic Kings promised religious freedom to their new subjects, but reneged immediately to exile or forcibly convert Spain’s Jews. The Muslims were unmolested until 1501, when they were also converted or driven out.

It has to be said that Isabella was quite a piece of work. In addition to initiating religious persecution and establishing the Inquisition under her personal confessor Torquemada, she had her own daughter Juana tortured for having heterodox religious ideas, hanging her from a rope while tying heavy weights to her arms and legs. Juana (aka Juana the First of Castile) was later known as “Juana the Mad,” and you have to wonder how she got that way. (Actually the men who claimed she was insane were those who achieved power by kicking her off her throne, so it’s possible she was as sane as 16th Century Spain permitted anyone to be.)

Naturally there’s a movement to make Isabella a saint, though it seems to have been derailed on account of that whole religious persecution thing.

Granada had been in Ferdinands and Isabella’s sights for some time. The quarterings of their royal arms show the areas they already ruled: the castles of Castile, the lions of Leon, and the red-and-gold stripes of Aragon. Below the shield they placed the pomegranate of Granada, as a way of showing “This is what we get next.”

After they conquered Granada, the pomegranate was inset into the bottom of the escutcheon in what the heralds would call an enté en point, basically a kind of wedge-shaped insert.

(Granada means “pomegranate,” by the way. Early grenades received their name because they supposedly resembled pomegranates.)

So. The Alhambra.

Alhambra might mean “the red thingie,” or “the red fort,” but nobody really knows. It was a ruined castle on a steep hill rebuilt in the 11th Century by the Jewish vizier Samuel ibn Naghrillah, also known as “Samuel the Prince.” Construction continued till the end of the 14th century until the place became a palace/city— actually six palaces, plain on the outside but lavishly decorated within. The palace(s) are liberally supplied with water through acequias, which feed the fountains, gardens, and pools so prized by Muslims.

The first thing you see after presenting your passport and entering, however, isn’t a ruddy Moorish palace, but a giant white palace in the Renaissance neoclassical style. The Alhambra was used by the Spanish as a palace after the Reconquista, and Ferdinand and Isabella lived there, as did their daughter Juana and her husband Archduke Philip of Austria. Their son, Carlos I of Spain (who was also the German Emperor Charles V), was concerned over the deterioration of the Alhambra and built the new palace in the European style, which required demolishing parts of the old building.

The new palace was never completed, because Carlos’ son Philip II moved the capital to Madrid and built new palaces there and at El Escorial. The Alhambra was still occasionally used, but parts were destroyed or reconstructed, and the art suffered.

Two very unique things about the Alhambra. First, there are no kitchens. The Kings of al-Andalus were concerned about preserving their nomadic Arab heritage, so all cooking was done out of doors over open fires. Second, the kings lived in very modest circumstances, in a part of the palace that resembled a long, narrow hallway. Again, this had to do with maintaining a simple lifestyle.

The kings’ private room was next door to a giant, splendid throne room, but that was to impress outsiders.

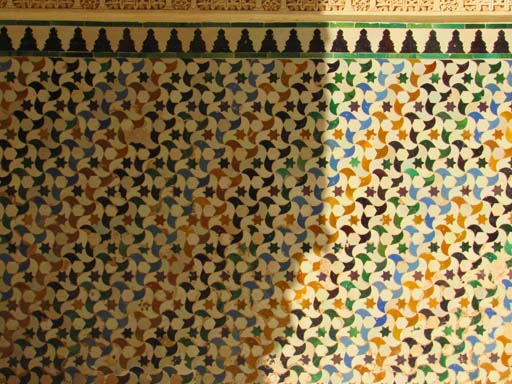

Still, there is plenty of opulence to go around. Indoors, the lower part of the walls are covered with brilliant tiles in geometric or mind-altering patterns. Above, the walls appear to be lavishly carved, but this isn’t stone, but gypsum plaster, cast in molds and then mounted on the walls. Originally the plaster would have been brilliant with color, but the color has faded.

Outside, the intricate plasterwork just glows in the sun. Geometric design, floral motifs, the coat-of-arms of the Nasrid dynasty, and Arabic calligraphy, some it poetry, plus many repetitions of the Nasrid motto, “There is no champion but God.”

The palace(s) are built around a series of courtyards, most with gardens and water features. The views of Granada from the balconies are spectacular.

The Alhambra continued to deteriorate over the centuries. Squatters moved in. In the Napoleonic Wars the French destroyed part of the complex in retaliation for something the Spaniards had done.

The American writer Washington Irving, assigned to the American embassy at Madrid, moved into the Alhambra in 1829. The resulting literary work, Tales of the Alhambra, became an international bestseller, and tourists began turning up. The Spanish were embarrassed into sprucing up the Alhambra, and it’s become a major attraction in the years since— the second most popular after the Gaudi cathedral in Barcelona. There’s really no place like it.

A plaque to Washington Irving has been installed in the rooms where he stayed.

Near the Alhambra is the Generalife, which sounds like the name of an insurance company, but may be derived from the Arabic janna al-Arif, “Garden of the Artist”— but it probably isn’t, nobody knows where the name comes from. This is a summer palace where the kings could go for a little hunting or R&R. The area between the palace and the Generalife are filled with gorgeous terraced gardens, most of which date from after the Moorish period. (The Duke of Wellington donated the English elms that shade the garden.) During the Moorish era the terraces were filled with the modest dwellings of the palace workers, but the hutments have vanished and been replaced by flowers and trees. I would have enjoyed spending a few hours strolling the gardens, but I was exhausted, hot, and dehydrated after hours of wandering through the palace, and all I craved was drink, food, and air conditioning.

We found a restaurant on a tree-lined boulevard a short distance away, and the usual lavish meal ensued.

Our hotel turned out to be quite monumental and stately. Again, I would have liked to have strolled through the streets of Granada, which are well worth the look, but we were exhausted and collapsed into siesta, rising only for dinner. After dark we ate a few streets away at the Giaconda cafe, on a plaza with two similarly-sized cafes that served different customers. One was for retirees, one for students, and Giaconda was for families. The waiter didn’t speak English but we managed excellent communication, after which we drank beer and ate fried seafood while children played and danced all around us.

I have to say that eating out of doors at a small cafe was a perfect way to end a day spent gawping at elaborate royal palaces, a way of returning to real life after the end of a phantasia.

I was going to be returning to my normal life soon, and this was a welcome way to ease the transition.

Great writing thank you. So very informative.

Why “Boabdil” (from Abu-Abdillah)?

For the same reason people say “Moctezuma” (or, historically, “Montezuma”) when talking about Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin… Medieval Spaniards weren’t really very good at transliterating foreign names 😉

I mean, Cortés and his people called Cuauhtémoc Tzin “Guatimozín”…

Boabdil still doesn’t make that much sense to me, because it seems harder to pronounce than the fellow’s actual name.

Of course here in the USA we have all sorts of places spelled differently from how they are pronounced, like Yosemite, Tucson, Boise, Pedernales, Arkansas, and Mackinac.

And of course Massachusetts has Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg. Good luck with that one. I’d suggest “Chum-lee.”

(The name means “I fish my side, you fish your side, nobody fishes in the middle.”)

Comments on this entry are closed.