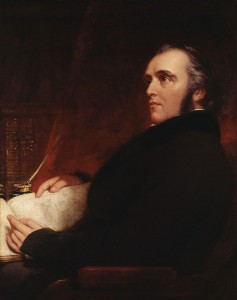

Babington

by wjw on July 24, 2018

Who was it who, on this blog, recommended to me the works of Thomas Babington Macaulay? I’ve searched but have been unable to find the comment.

Who was it who, on this blog, recommended to me the works of Thomas Babington Macaulay? I’ve searched but have been unable to find the comment.

Be that as it may, Macaulay has become my reading for much of the summer.

When I’m teaching at Taos Toolbox, there’s always the question of what to read when I’m not writing critiques of other authors. When I’m in full-bore critique mode I can’t read SF or fantasy for pleasure, and so I tend to default to history and biography.

My last year’s Toolbox reading was a Edward Baines’ A History of the Wars of the French Revolution, published in 1818 in something like eight volumes. The style was, well, readable, and served its primary purpose of calming my nerves and preparing me for sleep.

This year I thought I’d give Macaulay’s The History of England from the Accession of James II a try. It isn’t so much the history that has been carrying me through it, but the author’s style. He is so good at describing parliamentary controversies that I’ve been tempted to rework Quillifer II to include a lot more parliamentary debates. (Though, you will be relieved to know, I successfully resisted the temptation.)

And as for his description of personalities, try this one on for size, in reference to an admiral named Torrington: “The people readily forgave a courageous open-handed sailor for being too fond of his bottle, his boon companions and his mistresses and did not sufficiently consider how great must be the perils of a country of which the safety depends on a man sunk in indolence, stupefied by wine, enervated by licentiousness, ruined by prodigality, and enslaved by sycophants and harlots.“

You won’t find a passage like that in the works of a modern historian. Alas.

What you find in Macaulay is moral certainty. History and writing was a sort of sideline for him, and his real job was being a Whig politician. He believed in progress, reform, education, and rectitude, though his program was always a practical one, as coming from a practicing politician whose theories are always limited by the necessity of adhering to what is possible.

His sympathy for subject peoples, it has to be said, is more theoretical than real. While he deplores the tyrannical behavior of the English toward the Irish and the Scots Highlanders, he frankly refers to the Gaels as barbarians, and is particularly severe on Irish indolence, inebriation, and reliance on the potato. He doesn’t seem to quite comprehend that if the Irish practiced the sort of hard work and industry of which he approves, the English would have just taken it away from them and they’d be left where they started.

After Toolbox I found some other reading, but none of it had the charm of Macaulay, and I’ve been returning to the history in large and small doses ever since. I’m one of those readers who can just sink into an author’s style, and Macaulay is well worth sinking into.

Who was it who, on this blog, recommended to me the works of Thomas Babington Macaulay? I’ve searched but have been unable to find the comment.

Who was it who, on this blog, recommended to me the works of Thomas Babington Macaulay? I’ve searched but have been unable to find the comment.

I started re-reading the Praxis series in anticipation of The Accidental War, and have come to one inescapable conclusion: Sula is going to end up as Empress! lol! (Really looking forward to the next book.)

If you really want to have some fun, try Macaulay’s essay on Barère.

Or Macaulay’s essays on Milton and Machiavelli.

Is it the same or separate essays?

Comments on this entry are closed.