Something About Cabell

by wjw on April 29, 2018

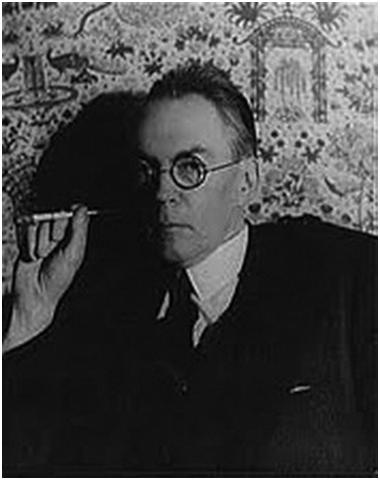

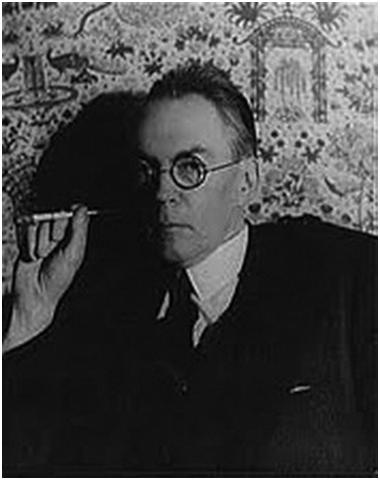

I have lately been revisiting the works of James Branch Cabell. (rhymes, by the way, with “rabble”)

I have lately been revisiting the works of James Branch Cabell. (rhymes, by the way, with “rabble”)

Insofar as Cabell is remembered these days, it’s as a writer of fantasy fiction. The best of his fantasies were reprinted in the Sixties as part of Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy Series, which is where I found him when I was a teenager. I haven’t reread him till now.

He’s part of a different fantasy tradition from what we see today. In his heyday, the teens and twenties of the previous century, fantasy could be High Literature, and that’s where he and his ambitions placed himself. He’s in the same literary niche as Lord Dunsany, say, or Arthur Machen, or Oscar Wilde, but not in the pulp tradition of Robert E. Howard or Lovecraft’s circle. And he was considered literature (when he wasn’t considered obscene), and was paterfamilias to a Southern literary scene that included F. Scott Fitzgerald, H.L. Mencken, Ellen Glasgow, Carl van Vechten, and Eleanor Wylie. His admirers include Mark Twain, arch-modernist Edmund Wilson, Michael Swanwick, and Neil Gaiman.

He was a Virginian, and presented himself in the tradition of Southern gentleman, and spent a lot of time working out his genealogy, apparently to improve his mother’s reputation within the small circles of the Southern gentry. His own reputation in those circles suffered from suspicion of homosexual orgies in college and of having bumped off his mother’s lover. Both false, apparently, but they gave him a sort of louche public character that he never overcame.

Most of his fantasies are part of the 18-volume Biography of Manuel, and take place in the fictional French province of Poictesme. They are droll and ironical, and have subtitles like “A Comedy of Appearances” or “A Comedy of Justice.” (Heinlein’s Job: A Comedy of Justice takes its subject matter from Cabell, and features Cabell as a character, but I strive to avoid books from Heinlein’s Dreadful Period, and haven’t read it.)

Cabell’s books mock themselves as they go along, and mock the chivalric romance also. Cabell can’t quite refrain from making the same point over and over again, which is that humanity is moderately ridiculous, human endeavor is pointless, and that human ambition is delusional (but necessary).

(Imagine a modern fantasy writer committed to this point of view— but of course you can’t. Perhaps you’d have to be born in something like the ruins of the Confederacy for that to make sense to you.)

On rereading Cabell I was reminded of my impressions when I was a teenager, which was that he loved repeating his thesis a little too much. A good reader would catch it the first time; every other reader would catch it on the second go-round; and after that it became just a little tedious.

The reason it isn’t fully tedious is Cabell’s prose style, which is simply wonderful, and which carries the reader right along, often through its sheer beauty. Some of his prose is in fact poetry— he would write a poem (a pretty good one, too), and then take it out of stanzas and put it into paragraphs of prose, and you encounter these little gems and have no choice but to stop and admire them. Cabell’s prose was clearly an influence on Jack Vance, Fritz Leiber, and Clark Ashton Smith.

Ballantine may have done Cabell a disservice by reprinting only the fantasy. Many of Cabell’s novels have contemporary or historical settings, though some were rewritten to fit somewhere in the Biography of Manuel.

And sometimes they surprise you. I recently read for the first time The Rivet in Grandfather’s Neck: A Comedy of Limitations, which is set in 1890s Virginia, in Cabell’s fictional town of Lichfield. (Recall what a “lich” is, and you may discover Cabell’s view of the postbellum South.)

TRiGN is a social comedy, involving the middle-aged, chivalric, but somewhat mediocre Colonel Musgrave, who marries a young Yankee belle half his age, the daughter of a millionaire who was born poor white trash in Lichfield, but who went to New York to make his fortune. The sort of complications ensue that might be anticipated when the subject is a May-October marriage, and the young wife has all the money, and the husband nothing but shabby gentility. The story would be tragic in the hands of a writer less committed to drollery, and I won’t give you spoilers.

But anyway, young Patricia isn’t in Lichfield very long before she scopes out the situation, particularly that of the black housekeeper, significantly named Virginia, and she gently confronts her husband about the town’s principal secret. The actual scene is couched in elaborately genteel language, so I will deliver it mostly in paraphrase.

SHE: “Agatha told me about Virginia, and how she was raped by your uncle, and gave birth to a boy who was lynched in Texas.”

HE: “Surely there are other matters which may be more profitably discussed.”

SHE: “That colored boy was your own first cousin, and he was killed for doing exactly what his father had done. Only they sent the father to the Senate and gave him columns of flubdub and laid him out in state when he died– and they poured kerosene on the son and burned him alive. And I believe Virginia thinks that wasn’t fair.”

HE:???

SHE: “I think Virginia hates the Musgraves. I think she poisoned your dissipated brother with opium and let your sister die when she was nursing her.”

HE: “This is deplorable nonsense, Patricia. Nothing more strikingly attests the folly of freeing the Negro than the unwillingness of the better class of slaves to leave their former owners.”

SHE: !!!

HE: “You who were reared in the North are strangely unwilling to concede that we of the South are best qualified to deal with the Negro Problem. We know the Negro as you cannot ever know him.”

SHE: “There are no Negroes in Lichfield! There are only people of mixed race employed as servants by their cousins!”

HE: “You really shouldn’t talk about these things. It might give people a false idea of you.”

And then, this conversation over, the social comedy goes on. But it shows that Cabell didn’t spend his whole life in the South without knowing what was what. And perhaps, after all, his neighbors were quite right in thinking he wasn’t entirely respectable.

Previous post: Double News Day

Next post: Crawling

I have lately been revisiting the works of James Branch Cabell. (rhymes, by the way, with “rabble”)

I have lately been revisiting the works of James Branch Cabell. (rhymes, by the way, with “rabble”)

I’d regard “Job” and “Friday” as (partial) exceptions to the Dreadful Period. You might try them, but I’d be the first to agree that they certainly don’t hold up against the juveniles or the stories in “The Past Through Tomorrow”.

Sounds like Cabell might have been the only respectable one of the lot…

I’m reasonably sure that as a result of his years-long occluded artery, Heinlein suffered some brain damage from, effectively, oxygen deprivation. (In “Spinoff”, originally an article in the March 1980 Omni Magazine, he discusses the diagnosis, treatment, and all of the medical miracles used in said events that had been made possible by the space program.) His post-Time Enough for Love writing never fully recovered.

I don’t know if I’ll read this book, but I’m certainly going to quote the there are no Negros line every chance I get. Wow.

With a title like that, I’m going to have to at least attempt reading it.

Amusingly enough, there’s another novel titled “The Rivet in Grandfather’s Neck” (don’t bother to read it; it’s a bore). This cannot possibly be coincidence.

Comments on this entry are closed.