Genres Extinct

by wjw on February 3, 2016

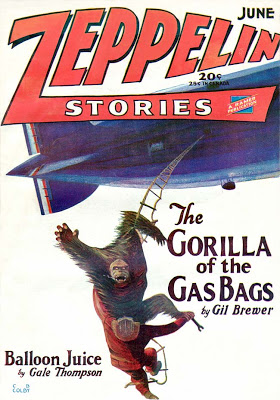

My recent post about Nevil Shute set me thinking about literary genres, and their rise and fall. Shute’s own particular niche is pretty well dead— not a lot of stories about zeppelins or epic aircraft flights being written these days. But Shute’s in good company.

My recent post about Nevil Shute set me thinking about literary genres, and their rise and fall. Shute’s own particular niche is pretty well dead— not a lot of stories about zeppelins or epic aircraft flights being written these days. But Shute’s in good company.

For example, I think we can safely say that the Homeric epic is dead. At one point producing a long narrative poem was a writer’s best chance of getting a Nobel Prize, particularly if it could be considered a national epic, a poem defining the peculiar spirit or nature of a people. With so many new nations being created in the early 1900s, there was a demand for a lot of national epics, and regional poets answered the call. But nowadays I’m not sure authors like Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Carl Spitteler, and Władysław Reymont are much read outside their native countries. If there.

I think we can also safely state that the Gothic novel is dead, both in its original Castle of Otranto form and in the Victoria Holt-style popular romances of the mid-20th Century. I’m guessing that in an era of serial killers and terrorists, no one’s really scared of spooky old castles any more, and modern women have a lot more options than to sit around in a dusty mansion waiting for Uncle Silas to bump them off. Though Gothics occasionally reappear— Thomas Disch’s The Priest comes to mind— they tend to be pastiches, satires, or learned commentaries on their predecessors.

Other genres may be considered Lost— the Lost Race story and the Lost World story, both fading when all the empty spaces on the map got filled in, and when the Hollow Earth turned out to be full of lava.

The Dream Narrative (Dream of Scipio, Romance of the Rose) has been extinct for so long that most people don’t know it ever existed.

After-the-Bomb stories seem to be dead, though dystopian and post-apocalyptic fiction otherwise flourishes in non-radioactive environments. I’m guessing After-the-Bomb died of the combined effects of the end of the Cold War and the publicity given nuclear winter, where it became clear that the Bomb wouldn’t just clear away the annoying parts of civilization, like taxation and bureaucracy, to leave the world a place where Men could realize themselves as Real Men in a landscape strongly resembling the Old West (only with mutants), but would instead leave a world in which the Real Men got to starve to death in the freezing cold just like everyone else.

The only extinct genre that I actually miss is the one in which Nevil Shute excelled, and which was also inhabited by writers like Hammond Innes, Desmond Bagley, and the early Alastair Maclean (before he started writing to formula in anticipation of a movie deal). These stories features reasonably competent protagonists wrestling not only with some external conflict but with highly imperfect technology. Innes’ The Wreck of the Mary Deare, for example, deals with how two men alone can sail a derelict steamship. Bagley’s The Golden Keel has to do with smuggling carried on aboard a wind-powered yacht, and features many details about sailboats. Maclean’s South by Java Head is an open-boat adventure set in World War II, while The Guns of Navarone features mountaineering, explosives, and the Dodecanese Campaign.

Most of the works in this genre were some kind or other of thriller. (Shute’s weren’t.) The prototype would be Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands (1903), in which a couple of yachtsmen, investigating the Frisian Islands, discover the plans for a German invasion of England. While there is a thriller plot, and a damned good one, much of the novel is taken up with the details of navigating a small boat through sandbanks in the early 20th century, when there was no radio, no GPS, no motor, and a lot of fog.

As with other examples of Geek Fiction, whether these stories work or not strongly depends on the author’s skill at making the technical details interesting to a general reader. The stories mentioned above score pretty high in that regard.

But that whole style of novel faded away as technology changed. Two people navigating a modern ship might take up a few paragraphs, not a whole book. GPS, cell phones, text messaging, Google Earth, Google Maps, drone and satellite reconnaissance, and fly-by-wire technology have pretty much eliminated the imperfect, fallible machinery on which these stories were based. And while computer and IT technology is certainly imperfect and fallible, there’s not a lot of suspense in the details of installing a new mother board.

The genre could be resurrected, of course, but it would be a period piece, and would depend strongly on convincing a modern audience that there was a time, in the dim past, long before Facebook.

Previous post: Happy Weekend

Next post: Turtle Tag

My recent post about Nevil Shute set me thinking about literary genres, and their rise and fall. Shute’s own particular niche is pretty well dead— not a lot of stories about zeppelins or epic aircraft flights being written these days. But Shute’s in good company.

My recent post about Nevil Shute set me thinking about literary genres, and their rise and fall. Shute’s own particular niche is pretty well dead— not a lot of stories about zeppelins or epic aircraft flights being written these days. But Shute’s in good company.

> competent protagonists wrestling not only with some external conflict but with highly imperfect technology.

I still get a kick out of George O. Smith’s Venus Equilateral stories, and Colin Kapp’s Unorthodox Engineers.

Fond memories of The Golden Keel (villain: the taxman!) as of Trustee from the Toolroom. But on the broader question, Franco Moretti has some quantitative work on the rise and demise of genres – see also Cosma Shalizi

Henry, that article was sort of interesting, but actual concrete examples would have better made the point. (Would have taken it out of the realm of theory, though, and I suppose we can’t have that.)

I think you see a particular old slice of SF that tried to carry on those kinds of stories. An acquaintance once referred to some of Jerry Pournelle’s CoDominum stories as “stories he wrote as science fiction because it wasn’t fashionable to write about Her Majesty’s soldiers in darkest Africa any more.” I’m not sure that’s entirely true, but in retrospect, I wonder if there’s a nugget of truth to that notion.

I consumed a LOT of Alastair Maclean when I was younger – I was a precocious reader, and made my way through a lot of his work between 4th and 7th grade. This was around the same time my SF/F reading was becoming more serious. A single library trips might yield a mix including “Fear is the Key”, a Sturgeon anthology, a Heinlein juvenile, a Zelazny novel, and a WWII submarine tale.

Perhaps it’s not so strange that when I described my recently-completed manuscript to a friend, they said ‘Hey, that sounds a kind of like ‘Ice Station Zebra’ in space, only with an engineer instead of a spy as the protagonist.”

How does “The Martian” fit, do you think, as something of a successor to the competent geek tradition?

I think “The Martian” is archetypical Geek Fic. It was even crowdsourced to geeks as it was being written.

SF has indeed become a home to lost genres. People who might once have written historical fiction are now writing alternative history. I don’t know about the CoDominium stories, but S.M. Stirling has quite deliberately written stories invoking the pukka-sahab days of Imperium. And I suppose you can say that urban fantasy is deliberately invoking goth-fiction tropes, for all that the goths in question are a lot more modern than the Lombards.

Riffing off John Appel’s query about where the ordeal of Mark Watney of The Martian fits in, I think the odyssy of Erasmus in Anathem fits into a similar genre of. Neither is Castaway in Mars, for both the lone Martian and the many Terrans are striving to reunite, thanks to both modern and outdated tech but also in spite of it. Something more than satellite reconnaissance and RTGs was required because, time and again, the tech failed or the right tech was simply lacking. But for Watney’s goofy psychological resilience, ingenuity, and the ingenuity and risk taking by just about everyone, there’d’ve been no rescue and no story. Watney’s encounter with the dust storm and sciencing his way out of it seems pretty analogous navigating the shoals in a small not, in the fog.

I posit that Anathem is of a similar genre. So much of Erasmus’s picaresque, almost Huckleberry Finnish adventure is accomplished without the aid of high tech, aside from that brought only occasionally to bear by Samaan of the Ita. The rest of it was mostly a scrappy affair that barely came off, with improvised solutions all along the way. If you look at Stephenson’s other works – Cryptonomicon, The Baroque cycle, Reamde, you see that in spades: grandiosely picaresque adventures fraught with not enough of the right tools, but inhabited characters bringing several flavors of cleverness, ingenuity, fear, error, and guts to the proceedings.

> home to lost genres

Bring ’em on! I’ll take Nevil Shute over Tolkein any day.

Is this actually a dead genre, or one that mutates along with technology?

Looks to me like “The Big Short” fits the latter view: “reasonably competent protagonists” (yes) “wrestling not only with some external conflict” (check) “but with highly imperfect technology” (sigh). Also: “whether these stories work or not strongly depends on the author’s skill at making the technical details interesting to a general reader.” (hah.)

Whenever anyone mentions techno-thrillers the first name that springs to mind is Martin Woodhouse and his Giles Yeoman books, aprticularly ‘Blue Bone’ and ‘Moom Hill’.

Like Shute, Woodhouse has a solid science/tech background – which helps a lot, I think.

“The Big Short” has the advantage of being nonfiction.

And science fiction and fantasy have the advantage of not being real. However competent the protagonist of “The Martian,” and however accurate the science, he’s dealing with technology that the author pretty much invented. It works the way the author wants it to, and he’s free to litter Mars with exactly the gear his hero needs.

Whereas real steamships and zeppelins only worked the way real steamships and zeppelins did. It’s kind of a handicap.

That’s my problem with the whole steampunk genre. “Steam” just becomes a synonym for “magic.”

TRX: “Here, a copy of The Steam Engineer’s Handbook.”

Steampunk author: “YAAAAAHHHHHH!!!”

I’m a bit late to the party here, but wanted to note that the Gothic Novel is not completely dead yet. The recent movie “Crimson Peak” was intentionally written as a Gothic Novel according to the director (the amazing Guillermo del Toro). I think that’s partly why the film didn’t do as well as hoped for, modern audiences found the story flow stilted and “unrealistic”. If you haven’t seen it, check it out. Its worth watching just for the amazing mansion that was built as a single set on a sound stage (rather than each room being a separate set).

Comments on this entry are closed.