On to Ottawa!

by wjw on December 28, 2015

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) might be just a wee bit behind on their paperwork, because they finally got around to declassifying the U.S. Navy’s plan to invade Canada.

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) might be just a wee bit behind on their paperwork, because they finally got around to declassifying the U.S. Navy’s plan to invade Canada.

In 1887.

The U.S. and Canada were having a dispute over fisheries, so the enterprising Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Charles C. Rogers, USN, having just finished a covert mission to examine the defenses of Eastern Canada, penned a war plan for his chiefs at the ONI (which was itself only 5 years old).

And by “penned,” I mean penned. It’s still in Rogers’ handwriting, and you can view it here.

It’s only eleven pages long, but it’s the first contingent strategic plan ever committed to paper by the American military. Unusual for a Navy plan, it places the emphasis on the Army. One army will drive north up the Hudson-Lake Champlain-Richelieu River-Montreal, a second will go up the Niagara to Toronto, and a third will be carried to Halifax by the Navy, which will then be able to interdict maritime traffic on the St. Lawrence

After the preemptive attack on Halifax, The US Navy, considerably inferior to that of the British, will stay in port until their numbers increase to a parity with the Royal Navy.

The plan went all the way up to Civil War hero Admiral of the Navy David Dixon Porter, but President Grover Cleveland negotiated an end to the dispute, and the plan has languished in the ONI archives ever since.

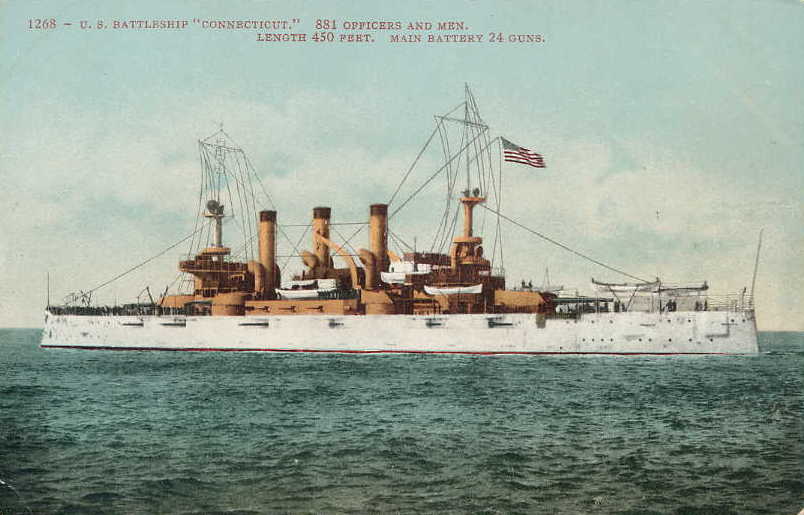

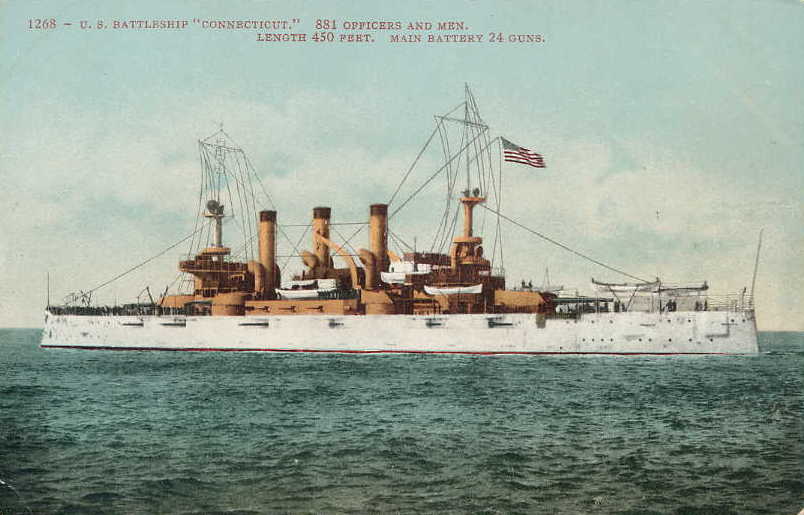

The plan was a result of changing technology and doctrine, with coal-driven battleships dominating the watery battlefield, telegraphs carrying news faster than horse-backed couriers, and overseas empires expanding. The Navy felt that it needed to take a more aggressive, possibly preemptive stance, and to have a permanent war fleet rather than a peacetime ocean-going police force that would ramp up in the event of war. Congress must have agreed, because they authorized the construction of two modern battleships and a heavy cruiser.

Naval planners continued to draw up plans against the likes of Great Britain and Japan, but canny American presidents kept foiling them by not going to war until 1898, when the plan against the Spanish Empire turned out to work very well. After which it was back to peace again, with Theodore Roosevelt (who has gone down in the popular mind as a belligerent jingo) negotiating his way out of a war with Germany during the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902, and sending the Great White Fleet into the Pacific in 1907 to foil a sneak Japanese attack on the Philippines and Pearl Harbor.

Of course a lot of that peace was made possible by the power of the Royal Navy, which enforced the Monroe Doctrine not because they loved President Monroe, but entirely for their own (highly commercial) reasons.

Now we have to enforced our own damned doctrine, and we have the bills to prove it.

And if the ONI is still planning to invade Canada, they’re not telling us.

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) might be just a wee bit behind on their paperwork, because they finally got around to declassifying the U.S. Navy’s plan to invade Canada.

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) might be just a wee bit behind on their paperwork, because they finally got around to declassifying the U.S. Navy’s plan to invade Canada.

*Somebody* in the Pentagon better have a plan for invading Canada. More than one plan, for that matter. And plans to invade everything else from the Vatican to China.

Should the need for a plan ever arise, some clerk ought to be able to find the appropriate filing cabinet and pull out a plan for the invasion of any place in the world. (or, in this modern era, locate the correct file and fire up the printers…)

Even if they’re old and obsolete, it’s better than a bunch of general staff frantically searching Google for an invasion plan should one suddenly become necessary…

My information is a couple decades old, but the last I heard, there were very few actual plans, and most of these involved engaging Soviet tank columns in central Europe.

We probably have plans for the people we can count on to be enemies, but twenty-first century reality seems to have caught us by surprise. Clearly we’ve had no plans for Rwanda, Libya, or Syria. We had a plan for capturing Bagdad, but no plan for what happened next. We had a plan for winning in Vietnam, but it failed.

Maybe plans are overrated.

Comments on this entry are closed.