Mr. Poe Requests the Honor of Your Presence . . .

by wjw on April 2, 2014

. . . at a great big ol’ war.

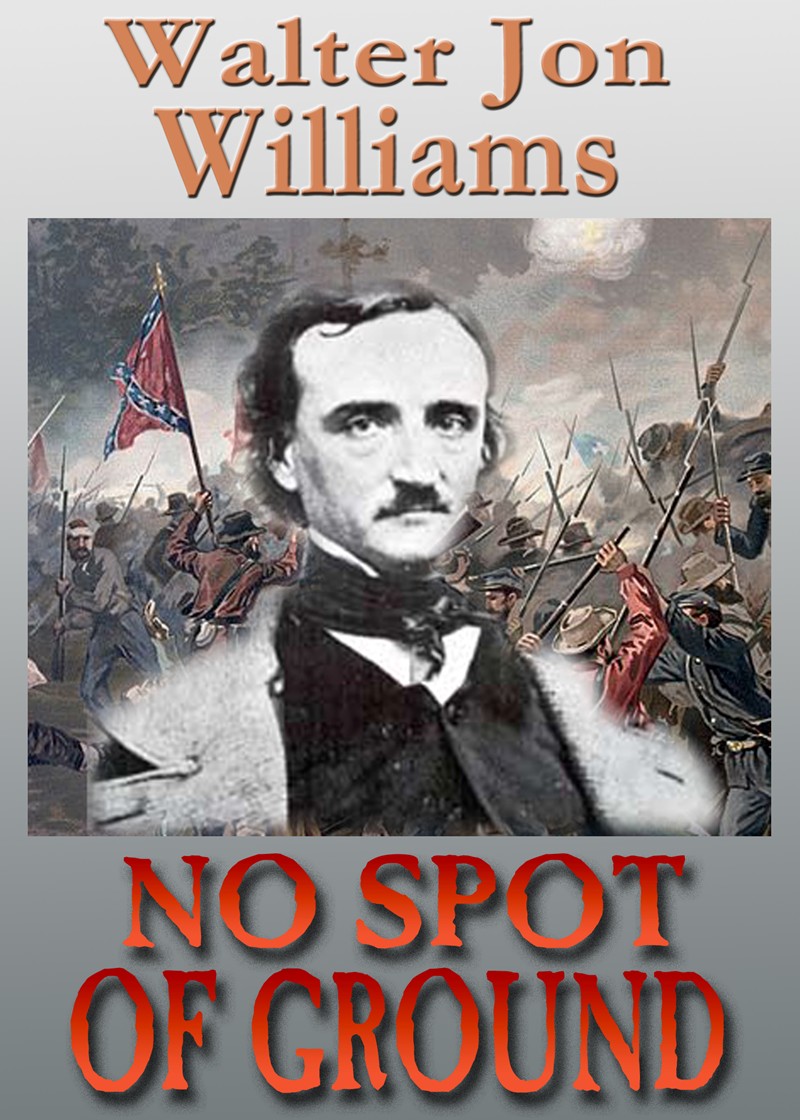

Which is all by way of saying that my novella “No Spot of Ground,” featuring the Civil War adventures of Edgar Allan Poe, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and Smashwords. It will appear on other forums presently.

Which is all by way of saying that my novella “No Spot of Ground,” featuring the Civil War adventures of Edgar Allan Poe, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and Smashwords. It will appear on other forums presently.

And it’s only $1.99! Less than two bucks for a short novel! What more do you want?

I have a fairly personal relationship with the Poe canon— but then so does everybody else, so far as I can tell.

I think that the first short stories I ever read were by Poe. I still have the copy of the Everyman’s Library edition of Tales of Mystery and Imagination that I found on my grandparents’ bookshelf, but (as their comprehension of written English was very limited) the book was in fact my father’s personal copy, a discard from his country grade school, which was across the highway from my grandfolks’ farm. Apparently he loved the book so much they just flat-out gave it to him.

I started reading it at the farm, then continued reading on the drive home, the kind of behavior that resulted in Lasik decades later. I was maybe eight years old, which is a little young for words like “illimitable” but just the right age for the terrors and sensations of Poe to smack me right between the eyes. Here was the inventor of the mystery story and (arguably) science fiction its very ownself. It was all the stuff I already liked, and here was more of it, only better! The Pit! The Pendulum! The Gold Bug! The Masque of the Red Death! The House of Usher! Murders in the Rue Morgue! I still vividly remember the visceral, and strangely ratiocinative, thrill of reading Poe for the first time.

I obtained a more sophisticated idea of Poe in college, when I took a Poe course from the late Pat Smith, who was a terrific, enthusiastic, well-informed teacher. Her interpretation was perhaps more Freudian than I would have liked (though not nearly as demented as Marie Bonaparte’s Freudian reading of Poe, which I absorbed with horror in grad school). In addition, we did the poetry, some of the essays, bits of “Eureka,” containing Poe’s metaphysical system (which prefigured the Big Bang, among other things), and we did The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Poe’s only novel. (He could never afford the time to write another one— he had to keep churning out short fiction and journalism in order to put bread on the table.)

What Arthur Gordon Pym did was bring me smack up against Poe’s racial attitudes, which were as imaginative and extreme as, well, all his other attitudes. Pym journeys to what I can only describe as the Heart of Blackness, finding Antarctic islands full of black people— by which I mean black all over, including teeth and eyeballs. The color white does not even exist on the island, and its alien presence unnerves the natives. These characters spend their time gambling, eating barbecue, and of course treacherously try to kill our heroes. At the end of the novel— as our heroes are about to plunge into Symmes’ Hole— we hear the gulls cry “Tekeli-li” as a giant shrouded figure “of the perfect whiteness of the snow” appears. Pym has reached the Heart of Whiteness, and his narrative ends.

(Jupiter, in “The Gold Bug,” is another stereotype, though it’s explained that Legrand has freed all his other slaves, but kept Jupiter because he was too feeble-witted to survive on his own.)

Poe was Boston-born and lived much of his life in the North, but he was Southern by training and inclination, and if he’d lived into the 1860s there’s little doubt that he would have supported the Confederacy.

So all this returned to my mind when Greg Benford asked me to contribute to his alternative-world anthology, What Might Have Been. (Which became Volume I when more volumes were commissioned. I believe this may have been the first-ever alternative-world anthology, though I can’t be sure.)

So I thought: Okay, Poe’s in the Civil War, how did he live so long, what does he do, and what does he do that’s Poe-esque. Cuz if he doesn’t contribute in some Poe-esque way, he’s not Poe, he’s just some guy.

Which leads to the question: Who is Poe anyway? A question that has too many answers: author, cryptographer, husband of his 13-year-old cousin Virginia. Inventor of mysteries, of science fiction, of psychological horror stories. Post-Romantic poet with a fondness for weird metrics (octameter catalectic, anyone?). Lover of pale dying women. Reviewer, essayist, philosopher, theorist of landscape gardening. How do you get all this into one story?

The answer to Poe’s character I found in his correspondence. His letters were so personal as to be beyond revealing. They were, in fact, the sustained shriek of an injured child, a child demanding love and attention from everyone around him.

In his stories he could pretend to be a grownup, but emotionally he was maybe ten years old. He was the smartest guy in the room, but he was a hysteric: inside he was so insecure and forlorn that he desperately needed whole hosts of people to feel superior to: blacks, Jews, philosophers, other writers. He was compelled to demonstrate that superiority over and over— cryptography, hoaxes, science and pseudo-science, vicious reviews that cut the legs out from his competition. He wasn’t a scientist, but he faked it well. He’d never been to sea, but whole chunks of Arthur Gordon Pym are filled with the details of sailing ships. He didn’t speak French, but he deployed his phrase-books so effectively that you’d think he was fluent.

And he faked being crazy, at least in his stories. And he did it so well that people decided he was crazy.

No wonder he wore out his welcome practically everywhere. It must have been exhausting to be around him. He was just this vast bottomless pit of need.

And so, with the correspondence giving me the key, I set out to construct my Poe. Insecure, demonstrative, emotional, defensive, half-hysterical, but the only guy in the story who knows what’s going on.

He does Poe-esque stuff. He does cryptography, he stages huge reveals for his chosen audience, he quotes Latin tags and French aphorisms, he vaunts his racial superiority over his bodyservant. He crushes perceived enemies like Baudelaire and his English publishers (who, historically, saved his literary reputation).

But by this point he’s realized he’s on the wrong side of history. The romantic cavaliers of Dixie are dead, and the war will be won by whichever side can build the biggest inhuman killing machine. Walt Whitman has upended the very idea of what a poet should be. No matter how talented he is, no matter the quality of his ratiocination, Poe can only lose. And it’s coping with that realization that lies at the heart of the story.

“No Spot of Ground” is the first story in what because a series, to which I’ve given the completely uncommercial title of “Dead Romantics.” They’re all science fiction stories about writers— done to amuse myself, really, but they seem to have found an audience.

For the title, I’m obliged to Pati Nagle, who reminded me of the line in Poe’s “El Dorado.”

As with my other historicals, every character in the story is an actual person, doing more or less what that person did historically, with the single exception of Poe’s slave Sextus.

I have inserted Poe into the Battle of the North Anna, which was a battle that Lee planned but that never actually happened because Lee and practically every other Southern general was too sick to fight. A battle that never happened is excellent material for an alternative history, and so, as it happens, is Edgar Poe.

And I was just wondering what to start spending my class action e-book credit at B&N on. Score!

I bought this and read it today with great pleasure. I am not usually a fan of alt history stories but this one worked for me. I know a little Civil War history and your setting for this story rang true to me.

Could you give us a list of your “Dead Romantics” stories? Am I correct in guessing that your “The Last Ride of German Freddie” is one of them?

Yes, indeed, Freddie’s last ride is part of the series.

Others are “Wall, Stone, Craft” and “The Boolean Gate.” I haven’t quite made up my mind whether “Red Elvis” is part of the series or not: it doesn’t feature a writer, but it has much else in common.

There are at least a couple more that I want to write, when the stars are right.

Thank you for answering my questions. Maybe one day your “Dead Romantics” stories could be put together as a collection.

By the way, if I may offer a suggestion, another of your stories that I would love to see made available for Kindle is “Broadway Johnny”. That is one of my favorites and I regret that you have never done anything more with the title character. When I first read that I hope it would be the first in a series.

John, you’ve got pretty good instincts there. “Broadway Johnny” was intended as the first of a series, but other work intruded and I never wrote the next installments.

It’ll be up fairly soon.

Excellent!

Very interesting to have my judgement that that story was meant to be the first of a series confirmed. May you one day be inspired to give us the sequels.

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2014/04/edgar-allan-poe-statue-boston

Since this started out with a story about Edgar Allan Poe, I thought I should point out something I just ran across over at Tor.com: Poe is going to be honored with a statue in Boston, his birthplace, this year (a picture of the statue is included in the story). Address above.

Poe romanticized failure and death so consistently that I don’t think he’d have known what to do with a triumph.

I don’t think he -wanted- to “win” in any conventional sense, except maybe to have a wonderful posthumous reputation as a writer and poet.

Which he got.

PS: it isn’t necessary to look for elaborate psychological reasons for Poe considering black people inferior. Virtually all white people in his period did, including many quite radical abolitionists. Lincoln certain did, then.

You could have gotten every white person in antebellum America who -wasn’t- a racist into Fauneil Hall and not packed it very densely. It was literally a fringe-crank position before the Civil War, and closely associated with other weird fads like crazy diets or communes in the woods.

You can just sort of assume that’s typical of everyone. It’s those who -weren’t- which require some special explanation.

It’s not so much that Poe was unique in being a racist, just that his version of racism was as unique as the rest of his notions. Taken together, it’s all part of the same pathology.

Comments on this entry are closed.