The Gallery of Whaam

by wjw on April 24, 2013

The weather was dubious in England, and Kathy is up for knee replacement and really isn’t good on cobbles or stairs or whatever, so we spent a lot of time indoors in art galleries and museums. And seeing a whole lot of art n a short amount of time sent certain ideas floating up to my attention.

The weather was dubious in England, and Kathy is up for knee replacement and really isn’t good on cobbles or stairs or whatever, so we spent a lot of time indoors in art galleries and museums. And seeing a whole lot of art n a short amount of time sent certain ideas floating up to my attention.

First, it’s easy to tell the genius stuff from the merely first-rate. I remember standing two whole rooms away from one particular painting, glancing at it, and saying “Vermeer!” Because, y’know, the genius just jumps out at you, even at a distance.

Secondly, it’s easy to tell both the genius and the first-rate stuff from everything that isn’t.

Thirdly, time is great at concentrating value. The National Gallery is probably in the running for the award for most-masterpieces-per-hectare, because it’s devoted to works that have stood the test of time. The Tate Modern, on the other hand, isn’t, because it’s devoted to works of the 20th Century, and it’s not clear which of these is valuable or not.

Though, to be totally honest, in most cases it’s kinda clear. The Tate Modern is full of art that was, in its time, experimental, and it’s a sad fact that most experiments fail. And just as in other galleries, the stuff that was genius just jumped out at you. And then there was the stuff that wasn’t genius but could be described as “interesting.” And then the stuff that wasn’t genius or interesting, of which there was a lot, and you can only think, “Those guys musta had great PR.”

Most of the real great stuff was just chock-full of passion and emotion. Even if it wasn’t clear that the emotions actually were, and even if the emotions were buried under layers of abstraction, they were there. They stirred you.

Or not. I looked at a wall of photographs, and I said to myself, “I’ve taken lots more interesting pictures than this. But I didn’t think to put a frame around them, hang them on a gallery wall, bill myself as a ‘minimalist photographer,’ and charge five grand apiece.” When they ran the ad in the paper for that job, why didn’t I see it?

There’s a kind of myth that modern art is impenetrable, and in fact it’s not. (Okay, maybe it was in the days when Fauvists and Cubists were battling it out with thick manifestos, but not any more.) Most modern art is based on a simple idea (“art is flat,” say) done with utter, deadpan seriousness. The more solemnity in its conception and execution, the more it’s supposed to be art. Most of it’s perfectly accessible to the layman, but not all of it is worth accessing.

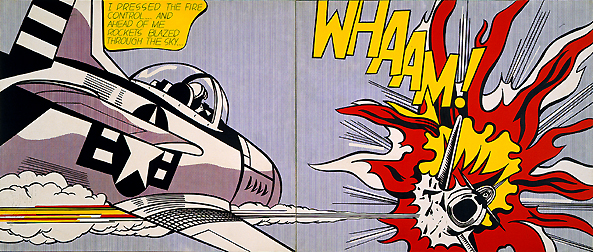

Musing thus, I walked from all the dark, depressing postwar British galleries into the Roy Lichtenstein special exhibit, and there was all this wonderful color, and humor, and joy, and I said to myself, “Yeah, I’m home!”

Lichtenstein has the same simplicity and dead pan as the other guys, but he’s not hiding his sense of humor. And he’s stealing like a bastard, sometimes reproducing specific images from comic books, sometimes appropriating paintings by his contemporaries and doing them all in his own style.

(As an aside, I wonder if someone like Roy Lichtenstein is even necessary any more. Instead of taking a panel from a 1963 issue of All-American Men of War and reproducing it as a diptych twelve feet across, why not just scan the original and blow it up to twelve feet? It’s neither more nor less appropriation than it was the first time, not really. Instead of Warhol creating faux Brillo boxes, why not use real Brillo boxes, just as Duchamp used a real urinal? But I digress.)

What I realized (and this is my fourth point, for those of you still counting) is that the stuff that engaged me was telling a story. It wasn’t always clear what the story actually was, but it was there. It was engaging me in a kind of dialogue. And the stuff that was best at dialogue was the more modern works, the ones where it was less clear what the story was.

That’s where painters like Norman Rockwell fail for me. He tells you a story, but he tells you exactly what the story is, and how he wants you to feel about it, and then it’s over. Compare with another American realist like Edward Hopper, who is also telling you a story, a story loaded with just as much emotion as Rockwell’s stories, but it’s unclear what the story is, and it engages the viewer’s imagination, and ends up a much more interesting experience.

So I was pontificating about this at lunch with the editor Darren Nash, and he said, “It’s the same with literature, isn’t it?”

Well yes, it is. The books that resonate with me are the ones that raise more questions than they answer, and that have me thinking about them hours, days, years after I’ve finished reading them.

This apparently puts me in a minority of readers. Best-sellers like The Da Vinci Code tell you exactly what to think, and answer all its own questions, and tie everything up, so that you can put the book back on the shelf and more or less forget about it for the rest of your life.

It has to be admitted that I strive not to do that. Even if I tie up the plot, I try not to tie up the world or its ideas. I strive to send the work out into the universe, as it were, so that it maybe resonates with everything else out there. I’m trying to engage you in a dialogue— and not just you, but everything you’ve read and seen.

Now that’s not too ambitious, is it? I’m thinking not. I’m thinking it’s something done by just about every writer that I admire.

Because we’re displayed in galleries, too. Except that the galleries are inside our reader’s minds, and everything on the gallery wall is talking with everything else.

The weather was dubious in England, and Kathy is up for knee replacement and really isn’t good on cobbles or stairs or whatever, so we spent a lot of time indoors in art galleries and museums. And seeing a whole lot of art n a short amount of time sent certain ideas floating up to my attention.

The weather was dubious in England, and Kathy is up for knee replacement and really isn’t good on cobbles or stairs or whatever, so we spent a lot of time indoors in art galleries and museums. And seeing a whole lot of art n a short amount of time sent certain ideas floating up to my attention.

“The Testament of Gideon Mack”, by James Robertson. I read it five years ago and I’m still thinking about it.

I don’t mind Lichtenstein’s comic art, but I guess I’ve never understood why it’s supposed to be better art than the original comics, despite dubious explanations by art critics.

The best films, books, and graphic art all leave you to think about something. Unfortunately, I think commercial success, lies in telling people what they should think, rather than stimulating them to think.

“I’ve never understood why it’s supposed to be better art than the original comics”

Art doesn’t happen without an observer. By observing this random contextless panel from a comic, and trying to invent a reason how it could possibly be art, you are creating a work of art through observation and introspection. It’s the observer effect as applied to artwork.

Also, the fact that Lichtenstein changed it so it’s an F-86 exploding instead of a MiG-15 is either incredibly significant or a completely irrelevant screwup.

Good point, DD.

The odd thing is that I remember reading the original comic when I was a kid, and Lichtenstein picked a really odd sequence to reconstruct. It’s a dream sequence in which Captain Johnny Cloud (“The Navajo Ace,” riding his Mustang through the skies and dogfighting Germans) is for unexplained reasons hallucinating that he’s in the Korean War, flying a Sabrejet and fighting MiGs.

So Cloud’s blowing up an F-86 us the least of the sequence’s mysteries, I’m thinking.

Comments on this entry are closed.