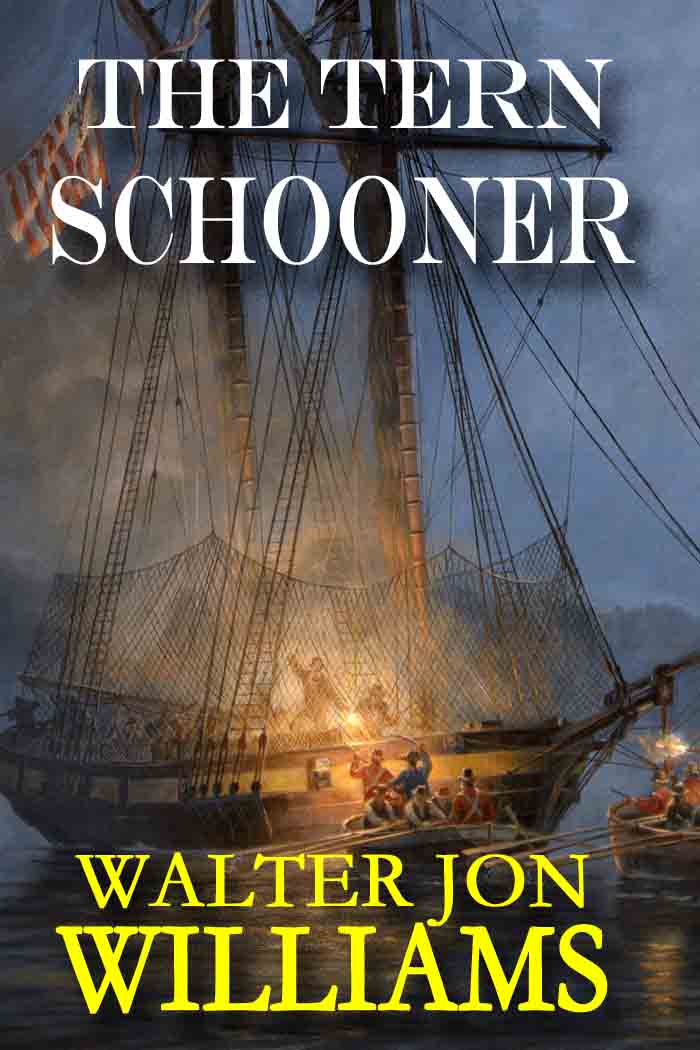

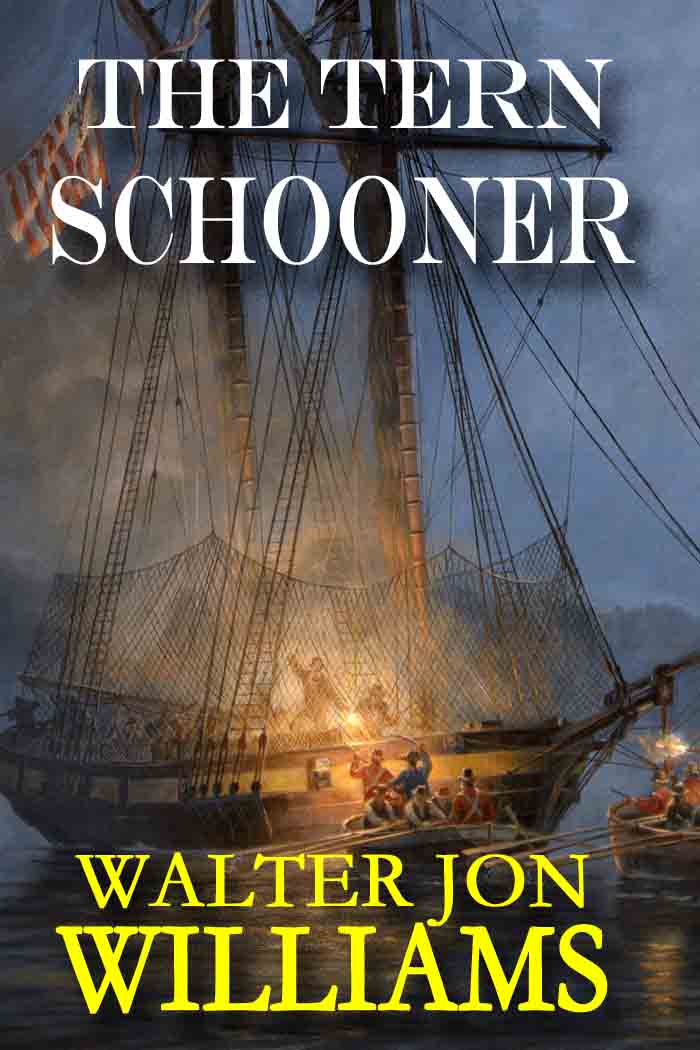

The Tern Schooner

by wjw on October 11, 2012

Behold! The Tern Schooner, the latest in the ebook reissues of my old sailing series, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords.

Behold! The Tern Schooner, the latest in the ebook reissues of my old sailing series, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords.

The book was originally published by Dell as The Yankee, in the same month and from the same publisher as The Yankee by Dana Fuller Ross. (Because Dell was just a fiasco in constant motion, that’s why, fascinating to watch if it wasn’t your career being made to walk the plank.)

I know I said I’d release Cat Island next, but once I got into the book, I realized that it involved characters and situations introduced in The Tern Schooner. So this one goes up now, and Cat Island in a week or two.

Unlike the other War of 1812 books, this one doesn’t deal with Favian Markham of the Navy, but rather his privateer cousin Gideon.

Gideon is an unusual action hero, in that he’s a convinced Puritan. But then what the hell, if Robert E. Howard could write about a Puritan swashbuckler, so could I!

I’ve long been interested in people who choose an inconvenient ideal to live by and then work it out in excruciating detail— the Brodainin warriors in Ambassador of Progress are another example— and so with Gideon, who spends a good deal of anguished time trying to work out whether or not he’s damned.

(Sounds like such fun, doesn’t it? But really, there’s enough action to keep the book from getting all theological.)

I’ve embroiled Gideon in the various happenings in the Gulf of Mexico, 1812-1814, of which there were a lot.

There was the naval war with England— at one point, American privateers had Jamaica completely under siege. There were the Baratarian pirates under Jean Laffite. There was the Creek War, which started out as a civil war among the Creek Indians, and then spread to their neighbors— and once that war got going, the British supported the Creeks with money and weapons so long as they continued to fight the United States. They even raised a battalion of Creeks, gave them uniforms and training, and used them in an invasion aimed at Mobile.

Why Mobile? Because it was a relatively easy march from Mobile to Baton Rouge, which could cut New Orleans off from the rest of the country.

I throw Gideon into the thick of all this, which means he has quite a lot to do besides brooding on his sins.

I based some of his character on that of Stonewall Jackson, who credited the Almighty with his victories and who preached a completely uncompromising brand of warfare.

But Gideon needed to be human, and he needed something to care about other than his precious soul, and so I introduced a comely widow, Maria-Anna de Marquez, who carries a pair of pistols, rules the table at poker, and is as ruthless at finance as Gideon is at combat. Gideon is a good deal softer at the end of the book than at the beginning.

There are also some chapters, some flashbacks, that catch the readers up on other members of the Markham family. They don’t advance the plot directly, but they provide a glimpse into the web of relationships in which Gideon was born, and highlight aspects of the history that Gideon doesn’t experience directly. (In short, I beg the readers’ patience.)

As for privateering itself, it was pretty much the salvation of the old republic. The U.S. Navy was small, and though it won some remarkable victories at sea, it couldn’t affect the larger course of the war. (This doesn’t count the battles of Erie and Champlain, which were decisive.) The British managed to blockade most of the American navy for most of the war, but they couldn’t lock up all the privateers. There were too many of them, and there were more all the time. Despite being blockaded for the entire war, Baltimore sent out more privateers than any other city, almost twice as many as the next two. (One privateer, aptly named Midas, slipped past the fleet bombarding Fort McHenry and seized the pay chest for the entire British force.)

(This is by way of pointing out that Gideon’s privateering exploits aren’t at all farfetched.)

By the end of the war it was nearly England, not just Jamaica, that was under siege. According to the Lord Provost, American privateers seized something like 800 British merchantmen in the first two years, and the totals were only getting worse.

(Plus the American navy kept getting bigger despite losses to the British. In late 1814, three American sloops of war were built near Boston in a mere 35 days. All were at sea by the end of the year.)

At the end, the British peace commissioners asked the advice of the Duke of Wellington. That worthy replied: “I confess that I think you have no right, from the state of the war, to demand any concession of territory from the Americans. You have not been able to carry it into the enemy territory, notwithstanding your undoubted military superiority, and you have not even cleared your own territory on the point of attack. You cannot on any principle of equality in negotiation claim a cession of territory excepting in exchange for other advantages which you have in your power. You can get no territory; indeed, the state of your military operations, however creditable, does not entitle you to demand any.” And that was before the catastrophe of New Orleans.

Ah, the catastrophe of New Orleans. That’s coming up in the next book, Cat Island.

Behold! The Tern Schooner, the latest in the ebook reissues of my old sailing series, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords.

Behold! The Tern Schooner, the latest in the ebook reissues of my old sailing series, is now available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords.

Relatively easier to what is this marching from Mobile to Baton Rouge?

What this reminds one of, is the Texans thinking it would be so easy to march cross-country to New Mexico in the lead up to and during the Civil War. We know how that worked out ….

The Duke of Wellington stuff is new to me. The school books made it seem that we got our ass handed to us. Marching from Mobile to Baton Rouge may have looked easy on a map.

The Duke of Wellington was offered command in America, and turned it down. He said something to the effect of: “You don’t need another general, you need control of the Lakes.”

If there was one thing the British army was good at in this period, it was marching. I don’t know what the state of the tracks were between Mobile and the Mississippi, but if they were as good as the Natchez Trace, an army could probably have used it.

The British might not have prospered with this plan, but it’s hard to picture a worse outcome for them than what actually happened.

I know what they were like, and they were far worse than the Natchez Trace.

And that was pretty damned bad — read the accounts of Andrew Jackson’s travels to and from Natchez to Nashville on his slave trading business, for instance. This is when he really began to hate Indians.

Or read the mess that Aaron Burr got into running from New Orleans, hoping to get to maybe Savannah in time to escape Jefferson’s men out to arrest him for treason. In other words there were no trails at all, except a few Indian trails. But lots of swamp and bush and forest.

As well, the Floridas, of which the Mobile territory was a part — West Florida — was the property of Spain, and Wellington was tied down, determined to beat Napoleon via his Peninsualar Campaign — and the Spanish were his allies in that campaign.

Not even Jackson was able to march to the Floridas from New Orleans in his war of conquest of same.

It’s far more likely than not, that the wilderness would have handed Wellington his ass if Wellington had been so silly as to attempt such a thing.

There was nothing there yet — it wasn’t yet the ‘black belt’ of the cotton cash economy of slavery. Supplying an army would have more than difficult. And Wellington was about nothing if not supply. As well he’d learned the effectiveness of guerrillas in Spain, but he wasn’t the one doing that sort of warfare or directing it. What Wellington knew how to do so brilliantly wouldn’t have had a place in that Indian territory, whether the tribes there were allied with England or not.

The first land trails out of the Floridas were established with the domestic slave trade — slaves from the upper south shipped to St. Augustine, sold and forced to march to the new cotton country just opening up in Alabama and Mississippi.

Love, C.

Fascinating about Wellington. I wonder if he had Burgoyne’s troubles prior to Saratoga in mind.

I think Wellington realized that it was a lose-lose situation. If he won, folks would just say, “Oh, all he did was beat the barbarian, cowardly Americans.” If he lost, he’d lose his reputation.

It’s amazing how little the British actually knew about America. During the Revolution they seemed to think it was about the size of Sussex, and would as easily be overrun.

During the War of 1812, they had no real idea of the situation in the Gulf or how to approach New Orleans— one reason they tried to hire Laffite as a guide. They blundered up to the Plains of Chalmette, and then never quite stopped blundering.

Ooh. I found another quote from Wellington, unusually cutting, in regard to the New Orleans defeat and the death of Pakenham, his brother-in-law:

“I cannot but regret that he was ever employed on such a service or with such a colleague. The expedition to New Orleans originated with that colleague… The Americans were prepared with an army in a fortified position which still would have been carried, if the duties of others, that is of the Admiral (Sir Alexander Cochrane), had been as well performed as that of he whom we now lament.”

“…they seemed to think it was about the size of Sussex…”

Well, I can sympathize with them a little. I had the opposite reaction when I first visited England as a young man. I could not get over how small the place was! What they called mountains, I saw as middling sized hills. What they called rivers, I looked at and thought “Back home, we would call that a stream or a creek or maybe a trickle.”

On the other hand, I was also repeatedly amazed at how far back in time things went there. I was constantly being startled when someone refered to something as “new” because it was only 400 or so years old! Or looking over the archeological site where I worked for a couple of weeks as a volunteer: you could see traces left on the land by medieval plows, the marks of the huts of a Saxon village, a pottery kiln in use when it was a province of Rome and, everywhere, if you had the trained eyes to see them in the grass, flints shaped and used by men to whom Romans and Saxons were the undreamed far future.

Yes, my homeland is small – but beautifully formed.

It’s a pity that its modern inhabitants are working so hard to concrete it over!

John and Dave, to sum up the difference in perspective of the English and Americans:

“An Englishman thinks 100 miles is a long way. An American thinks 100 years is a long time.”

An excellent line, Mr. Wisham. It states with great pith and precision what I was trying to say in my prolix and clumsy fashion. Who are you quoting?

The PLAINS of Chalmette??????

I know it’s more accurately “the cane fields of Chalmette,” but it’s gone down in History as “the plains,” so there you go.

Hmm. I was looking up related issues online, and found that Jackson marched his army from Pensacola on November 9, got to Mobile on the 19th, and then went on to New Orleans— Jackson arrived with an advanced party on December 2, and the balance of his force by December 22.

All this marching was over land. So it +was+ possible.

Comments on this entry are closed.