Saw a couple of films noir recently, one a classic, the other more recent.

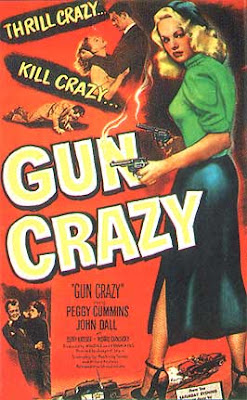

Gun Crazy (1951) was the classic, and was a pure example of the film noir— or, as we called them in America, B pictures. Made on the cheap, full of actors you don’t remember ever seeing before, and filmed on the streets in natural light because it’s less expensive than using a sound stage. Lots of gritty action, because that’s cheap, too, and scenes where the actors are improvising, because rehearsals cost money.

More importantly than any of that, the story followed Matthew Sweet’s First Rule of Noir: “Choose a dame with no past and a hero with no future.”

Other than this crucial element, the story rather lets the film down. There just isn’t enough of it. So the first part of the film is loaded with unnecessary flashbacks documenting the hero’s obsession with guns; and the last half hour is one long chase scene in which nothing happens but the chase scene. Gun Crazy could have been a one-hour TV episode, and maybe been better for it.

The plot: a marksman with no job, moderately bad, meets a markswoman who’s completely evil, a psycho killer. The two go on a crime spree— inspired by the careers of Bonnie & Clyde— and then there’s a manhunt, and the law takes them down. That’s sort of it.

The screenplay was by McKinley Kantor, who wrote the story on which it was based, along with blacklisted Hollywood communist Dalton Trumbo, using one Millard Kaufman as a front. I don’t think Trumbo had much control over this one, because it’s not as front-loaded with ideology as a lot of Trumbo’s dramas (in his romantic comedies, Trumbo gave a happy ending even to the bourgeoisie).

What you watch this one for is the direction. Joseph H. Lewis was forced by the lack of a budget into all sorts of expedients— where a normal director would use a number of cuts to give us information, Lewis would use deep focus to pack as much information into a single frame as possible. He’d use long, long takes, both because they were cheaper and because that meant the editor couldn’t screw with the final product. (And sometimes he did this to the point of absurdity— there’s one long talky scene where we mostly see the back of the actors’ heads, probably because the director hadn’t time to do a proper setup.)

And now and again Lewis takes us for a ride— he just puts a camera in the back seat of a car and follows his heroes as they go on a bank job. All one long take— maybe seven or eight minutes long, nearly a whole reel— with the actors frantically improvising dialog as they go. When one of them says, “I hope we find a parking spot,” he probably really means it.

The stars are Peggy Cummins and John Dall— and because they’re not big stars, Lewis can really screw with them. In the final scene, after the fugitives drag themselves up and down a mountain and through a swamp, they actually look like they’ve been in a swamp. You can’t imagine any actors with clout allowing themselves to be photographed looking so ugly and wretched.

Gun fetishism. Sex. Thrill killings. Who said it was the Boomers who invented this stuff?

If you’re hungry for a night of noir, and you’ve already seen Kiss Me, Deadly, this will suit you down to the ground, though you may be tempted to fast-forward through the final chase.

The new noir was Circus (2000), which was more of a thriller-noir-caper movie hybrid. It had all the bleakness and nihilism of noir, and all the intricate plotting of a caper movie. And it follows the rules of film noir— filmed cheaply, on the streets, with no big stars (John Hannah, Famke Janssen, Fred Ward, Eddie Izzard)— and with no expensive effects, other than a lot of squibs filled with fake blood. This is a film about English gangsters that’s bloodier than the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. (Do Brit gangsters really get that extreme?)

Hannah plays a con man, who’s married to a con woman, Janssen. He works for an evil psycho gangster who wants to get rid of him. He’d kind of like to get rid of the gangster, too, but he’s awfully preoccupied since he owes a lot of money to a violent bookie and he’s being set up for a murder that he actually committed, but which no one was supposed to know about. And maybe his wife wants him dead. As does the hit man boyfriend of the woman he killed. As does, apparently, everybody.

In this post-Tarantino world, all movie gangsters are required to have hobbies and eccentrities. For instance, in this movie Izzard is always expressing himself through 80s pop songs. It’s okay but you really don’t want it to go on too long.

Circus is one of those films where everyone’s playing everyone else, like House of Games or Bound or The Last Seduction, all of which I liked. And it’s a writer’s movie, which I like on principle.

The writer in question was David Logan, who doesn’t seem to have a lot of credits, but who manages to keep the threads of an incredibly complex plot from getting too tangled. If I worked out the ending ahead of time, it’s because I do this for a living. (By the way, I just wrote “threats” instead of “threads.” That works, too.)

But the best part is, this never stops being a B movie. You’ll never mistake it for Pulp Fiction or Body Heat. You get your cheap thrills, and then it’s gone, vanished into the night like the Woman in Red.

By the way, there is no circus in Circus. Go figure.

Noir

Previous post: Managers

Next post: Can You Do the Fandango?

Have you seen Brick? If not, it's a delightful mix of Noir with everyone's favorite genre middle American high school drama.

Comments on this entry are closed.